CHAPTER TWO: ‘THE CALL OF THE

TRANSGRESSIVE AND THE TABOO…’

Porn is often portrayed as a furtive, lonely and shameful pursuit. But as furtive, lonely and shameful pursuits go, it’s one of the best. ‘Don’t knock masturbation’ declares Woody Allen in ‘Annie Hall’ (1977), ‘it’s sex with someone I love.’ Most men look down on porn, but that’s only because to hold it up would only strain the wrist still further. Such magazines might corrupt and deprave their readers, ‘that goes in there, and that goes in there, and that goes in there, and then it’s over’ according to Jarvis Cocker, but it is also indulging in what Roxy Music-ian Brian Eno calls ‘hanging onto the only thing you can rely on’ (in his ‘A Year With Swollen Appendices’ Faber & Faber, 1996). Wankers form a clique more obscure than a Masonic handshake, united by a love that still prefers not to speak its name. ‘Les Plaisirs Solitaires.’ Yet Porn is always pretty good. And even when it’s bad, it’s never really that bad. There’s no excuse for porn. It doesn’t need one.

Is reading porn sad? It’s often seen that way. A sad solitary vice. But most people’s lives are sad. Or at least tinged by melancholy. What they call ‘lives of quiet desperation.’ What novelist Stan Barstow perceptively terms the ‘raging calm’. What exactly is it that you measure to determine a quality of life? Sexual satisfaction rates pretty high on most scales. You don’t need Freudian theory to tell you that. Of course, expectations alter. Low expectation-situations stoically endured by earlier generations, are now no longer accepted, or seen as acceptable. They suppressed and repressed what were deemed ‘unhealthy’ or even sinful desires. That’s no longer true. The hierarchy of need is a factor. As basic needs are fulfilled, others are magnified to take their place. Capitalism is another. Market forces amplify cravings they can then claim to satisfy. Then they escalate the dependency they’ve created. None of which is to deny the essential pulse. The need. The thirst for experience. The inability to resist the call of the transgressive and the taboo.

In sex, we may long to lose our composure, self-control, and even our separate identity, but there is one thing we desire even more, and that is not to lose control, not to lose our unique separateness. Books allow us the luxury of doing both.

Purchasing real extracurricular sex holds real dangers. Such as infection. That’s always been a major disincentive. Such as the Pimp on the stairs waiting to mug you. Such as the liberal guilt of exploiting the vulnerable, prostitution is not necessarily the simple rational-choice financial transaction it might seem to be. What if your money is fuelling her narcotic dependency, or if it’s forced upon her by an exploitational degrading abusive relationship, or compelled by illegal immigrant poverty sex-slavery? But then again, every human interaction carries with it a metaphorical balance sheet, an implied burden of obligation and reward, even pulling into a service station to buy petrol, you could be fuelling the cashier’s narcotic dependency, or funding some degrading abusive relationship. Morality can be complicated at times. Not to mention the more directly personal fears that just possibly the artificial nature of the transaction could result in a failure to achieve the required erection, or worse – premature ejaculation could mean you get less than full value for your money. Books are a one-way transaction. Porn carries no obligation, to anyone, other than self.

So efficiency is also a factor. Philip Larkin – in a letter to Anthony Thwaite, argues ‘why bother with girls when you can toss off in five minutes, and have the rest of the evening to yourself?’ It’s a quick fix without the complications of emotional involvement. To poet Tom Paulin, Larkin’s fondness for porn was ‘the sewer under the national monument Larkin became.’ But maybe he has a point? Get that itching need out of the way as quickly and effortlessly as possible, and free the mind to move on to higher things. Truman Capote suggests another benefit, unlike the rituals of seduction, you don’t even have to dress up. And unlike other social vices – say, smoking, alcohol or narcotics, masturbation is cheap and healthy, while its resulting emissions are neither toxic nor carcinogenic.

But let’s not take this too far… in exactly the same way that all those Clearasil overdoses never quite vanquish your acne, so the fast-food diet of the vulgar glamour-mag’s tawdry allure never quite vanquishes the jerk-off junkie’s prurient urges, not when you’re permanently drowning in unspent sap. And if every orgasm, as the Elizabethan’s believed, deducts a day from a man’s life-expectancy – paying for your pleasure with a small death, then my day’s are seriously numbered. While – unlike smoking, masturbation loses out as a socially interactive activity, unless we’re to advocate the ‘circle-jerk’ as an alternative role-model to the ‘Office Smoking Break’? Perhaps not an entirely feasible idea.

Wystan Auden calls desire ‘the most enticing of mysteries.’ He wrote his own rhymed porn in the form of “The Platonic Blow” – about a Gay tryst between the narrator and a mechanic. ‘Despite all the lyric or obsessive cant about the boundless varieties and dynamics of sex, the actual sum of possible gestures, consummations and imaginings is drastically limited’ opines George Steiner sniffily (in his essay ‘Night Words: High Pornography And Human Privacy’, in ‘Encounter’, October 1965). And sure, Porn reduces bodies to shapes of desirable colour enclosing highlighted interest focal-points that float in a triangulation of nipples and pubic hair. Breasts are there to be visually experienced. Legs are there to be parted. Sometimes girls with little more than hints of clothing can be more suggestive than naked girls, an exposed navel or the curve of skin bulging from a too-tight basque hints at the softness of the flesh beneath. At other times, nothing but total exposure will do. Yet surely, the pure and essential nature of a thing is not to be found in its technologically-reproduced image? The centre-fold is both real, and illusory. It is a high-gloss visual representation of a real woman, and the fantasy ideal you can never achieve.

In the 2006 movie ‘Venus’ ageing thespian Maurice (Peter O’Toole) and teenage Jessie (Jodie Whittaker) stand before the painting of ‘The Toilet Of Venus’ by Diego Valazquez, in which the naked reclining goddess observes herself in the mirror that cherubic Eros is holding for her. ‘For most men,’ points out Maurice ‘a woman’s body is the most beautiful thing they will ever see.’ ‘What’s the most beautiful thing a girl sees, do you know?’ enquires Jessie. ‘Her first child’ he answers. Perhaps Maurice borrowed the words from John Updike. A woman’s body is the most beautiful thing most men will ever get to see throughout their lives. I’m not about to argue with that. It’s not their fault they’re beautiful. They just are. And males get pleasure from that beauty. No matter what social or moral restrictions are applied to it. That’s not their fault either, if fault it is, which it isn’t.

Women who obsess about their imagined bodily imperfections are missing the point. Shared nakedness is a form of honesty that is beautiful in itself, simply because it is honest. But the way society operates, glimpses of that beauty are forever denied, except through ingenious stratagems devised to circumvent those conventions. Forcing the need to sate the thirst for beauty at one remove, via commercial transaction, or by proxy, through facsimile. High, or low-brow. Steiner, again, suggests that ‘what distinguishes the ‘forbidden classic’ from under-the-counter delights on Frith Street, is, essentially a matter of semantics, of the level of vocabulary and rhetorical device used to provoke erection. It is not fundamental.’ Botticelli’s model for his painting of ‘The Birth Of Venus’ was a Florentine prostitute called Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, painted nude for the titillation of his Medici client. The perfect elision of beauty, commerce, and sly deviance. Art is different, isn’t it? Art is elevating.

Agnolo Bronzino’s “Venus, Cupid, Folly & Time”, also commissioned by a Medici client, is a gridlock of limbs. A naked and clearly underage boy, his bottom pertly raised and angled at the viewer, is entwined with an equally naked woman. Her tongue slips into his mouth. His fingers tweak her right nipple. And more – read the script, they are mother and son, invoking the strongest of cultural taboos. But it – too, is art, disguised at one further move by its roots in mythology. And much later, Manet’s “Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herne” appalled his contemporaries by portraying a bizarre picnic of formally dressed men, with a single naked woman. But that’s art. Art is different.

Neither Peter O’Toole nor John Updike ever claimed that their assertion is true for all men, nor do they venture an opinion on whether the reverse holds true for women. ‘Your first child’ suggests Maurice. Not that appreciation of the male nude has not run a parallel riff through history, or that arousal is not a valid reaction to abstracted and impersonal portrayals of the naked male – to even suggest as much is to antagonise outraged reaction, merely that social and economic forces have conspired to ensure that the female nude is more prevalent and well-documented. Nevertheless, the implication of a vital link between the concept of beauty to sexual selection and hence to Darwinian evolution, are difficult to refute.

‘Big breaths’ says the Doctor on the saucy postcard. ‘Yeth, and I’m only thixteen’ brags the blonde Lolita he’s examining. ‘The male is obsessed with screwing’ declares feminist academic Valerie Solanas self-evidently, ‘he’ll swim a river of snot, wade nostril-deep through a mile of vomit, if he thinks there’ll be a friendly pussy awaiting him.’ Perhaps the lady underestimates the male sex-drive a wit? Surely it’s a tad more powerful than that? But in 1966 she sells her essay ‘A Young Girl’s Primer’ to ‘Cavalier’ in a further attempt to explain one sex to the other. And that’s got to be good. Just because the gulf between desires is unbridgeable doesn’t mean that it’s not a good thing to build bridges. So when exactly is sex sexy rather than prurient? At what point is sex educational rather than sleazy? When can sex be considered acceptable rather than embarrassing? After all, if my cunilingual skills are acceptably proficient – and I’ve had no complaints, then that’s due to diligently studying the technique of clitoral-tonguing described in ‘jazz-mags’.

And yet – despite visual evidence to the contrary, it is the penis that is really the central character of this history. ‘To have an erection in the morning… is to be alive’ says Philip Roth. Of course, the penis never appears in glamour mags. Yet everything within its pages is designed for its stimulation. It is the rising star that makes its appearance early, peaks frequently, and yet still persists throughout. It was ever thus. Michel de Montaigne’s ‘Essays’ (1580) details its familiar troublesome aspects – ‘one had reason to remark on the unruly liberty of this member that so importunately asserts itself when we have no need of it, and so inopportunely fails us when we have need of it… so proudly and obstinately refusing our solicitations, both mental and manual.’ Norman Mailer writes about the ‘grinding hound’ in his trousers. While Paul Theroux admits to having a ‘demon eel thrashing in his loins.’ Necessarily, it deals in more than one name, and frequent aliases in order to defend itself against tedious repetitions.

All of this could justifiably be accused of phallocentricity. Which is absolutely true. But this is a ‘Personal History’, so there’s no way it can be anything other than that. There’s a story by Ian R MacLeod in ‘Interzone’ magazine (no.34, March-April 1990), in which a prostitute uses a Swap-appliance in order to switch genders with her client, so that the woman can experience the sensation of penetrating, while the man can know what it feels like to be vaginally penetrated. Needless to say, the fictional outcomes are less than edifying. Perhaps if such a technology existed it would educate men to become more caring and considerate lovers? But until such a device comes online we can only conjecture. We can attempt an empathic connection. But we can never know, not on any real meaningful level. Individuals must always be alien one to another. Genders even more so.

And of course there are dark sides to male sexuality that are not always immediately obvious, insidious ones that relate to often subliminal and scarcely understood attitudes. To enter such mind-sets is not pleasant. It is frequently repellent. Yet to deny their existence is to perpetrate a dishonesty. Through some perceptions, women are desirable, but women are also frightening. They bleed. They become pregnant. Their vaginal secretions smell funny. They draw you in – moist, fleshy, alien – only to make you lose control, then overwhelm you. They’re unpredictable, with violent mood-swings that demand your reactions, even when you don’t know how to react. They mock you and ridicule you when you’re unable to measure up. They have the power to make you feel weak, inadequate – and dirty.

At some point, it could be argued, a man makes life choices. To be faithful (more-or-less) in a committed relationship, trying his best to be sensitive, concerned, loyal, caring, considerate, responsible, while making do with infrequent bored sex. While envying (sort-of) the unmarried guy who seems to be dating all those foxy affectionate girls. While that same unmarried guy is probably jealous of what he assumes to be a regular warm and comfortable married sex-life.

Women have the most valuable possession you can ever hope for. The purest, the most holy gift of them all. The one you want so much you ache from your intensity of yearning. The one thing that will make your life complete. They have the gift of transcendental beauty that they bestow, or withhold on the merest of whims. While they squander it on the most unworthy men. They trade it like a commodity. They devalue it in ways that mock and humiliate you. They coldly and calculatingly give it to rich old men. They get drunk and give it to silly young men who neither value nor deserve it.

And they laugh in your face. Reducing it to barter. To money.

This way lies madness…

Sometimes I disgust myself. Sometimes I hold myself in low esteem. And the male sex in general. Sometimes I think if I was a woman and had to select a potential partner from the devious sad losers of the men of my acquaintance, then I’d be better off not bothering. I’ve always thought that women, in general, are better than men. Men are mostly rubbish. The genetic after-thought. The second-stage womb-mutation. The necessary adjunct to reproduction.

What men do best is obsess. That usually involves a degree of unsociability and self-absorption which in itself can be unpleasant or distressing to those they’re supposedly close to. But it’s through obsessing that they contribute, or add to, or evolve things a little. That’s their mitigating circumstance.

This is my obsession. My contribution. My slight addition to the sum of things…

— 0 —

As a dedicated and long-time porn consumer, my story is also the low-down on the filth market. But where to start? Victorian essayist Thomas Carlyle observed that ‘all that mankind has done, thought, or been, it is lying as in magic preservation in the pages of books.’ Academics of erotica have a tendency to rummage through the accumulated remnants of humankind’s vast history to pluck forth overlooked images and texts that might create the desired shock of recognition among the cognoscenti. The explicit paintings on the walls of the brothel in lost Pompeii, illustrating the services available? The ‘Secret Museum’ (‘Musee Secret’) in Naples stores erotic representations from classical antiquity, and in particular the ancient world of Pompeii.

The opening chapter of Channel Four’s documentary series ‘The Secret History Of Civilisation’ (14 October 1999) begins precisely here, with the god Pan copulating with a goat. But it’s the written word that sets us apart from barbarism, allows us to reflect on the benefits of civilisation, and more exactly defines its limits. The luscious multi-gendered poems of Sappho were written some five hundred years BC. It is from her we get the term ‘sapphic’. Most of her poems are known only through surviving fragments, or from references to them quoted by subsequent writers. Perhaps copies of the originals were housed in the great Library of Alexandria, it was – after all, said to contain a copy of every manuscript then in existence. And they were accidentally torched in 47AD when – according to some accounts, Caesar set fire to his own fleet. The ‘road to ruin’ gets off to an early start.

Aristippus of Cyrene, Socrates’ pupil, was probably the first to assert the philosophy that hedonism is the highest good. But caution, pleasure carries its own hazards, as Epicurus pointed out later. He observes that the pleasurable life is not necessarily one that avoids all pain, because restraint is also a component part of pleasure. And while pleasure brings happiness, don’t the dissolute tend to die notoriously young? What’s that about living fast, dying young, and leaving a stylish corpse?

When Roman poet Ovid (43BC-17AD) embarks on his own career by composing an erotic elegy ‘Amores’ he would already have been familiar with Sappho’s texts. His tongue-in-cheek mock epic first suggests that ‘every lover is a soldier’, a metaphor that makes each seduction a campaign subject to wile and strategy. He later expands the theme with his lover’s tutorial ‘Ars Amatoria’ (‘The Art Of Love’), giving advice to the people of Rome on the playful guile of meeting potential partners – including the best places to ‘cop a furtive feel’, for example at the theatre where brushing up against someone is bound to happen. Then how to seduce and retain lovers, and finally the variety of positions in which that campaign of seduction can be consumated.

Although intended primarily for men – he provides a separate treatise giving equally frank advice to women, he notably advocates the importance of mutual passion, and the consideration a lover should devote to his partner’s pleasure. And while accused of ‘licentiousness’ his writing is seldom vulgar, advocating only that a forthright honesty is necessary, because ‘what you blush to tell is the most important part of the whole matter.’ Unfortunately his enlightened attitude to the mutuality of sexual fulfilment was to be eclipsed by the dour austerity of ascendant Christianity with its distrust of sex, emphasising the purity of matters spiritual, suspecting the physical world of the senses, and deferring rewards into some theoretical sexless afterlife.

Augustine of Hippo (354-430), in the Roman province of what is now Algeria, might have started out by saying ‘grant me chastity and continence, but not yet,’ but then he goes on to go beyond the ‘yet’ by framing the concept of ‘original sin’ on behalf of nascent Christianity. It must be recalled that, rather than the eternal inflexible truth of the divine it claims to be, Christianity was very much in the process of inventing itself, patching, editing and arguing out the mosaic of its beliefs into some sort of consensus. Drawing on his experience of the Manichean sect, and his dialogue over free-will versus inherited guilt with rival Church Father Pelagius, Augustine definitively expounds his idea in his ‘Against Two Letter Of The Pelagians’. Apparently, we’re all damned already, due to that spot of mischief in the Garden of Eden. The Fall from grace made sin an integral part of human nature. The sexual act, and the passions it enflames, is the way sin is passed down from one generation to the next. Life is a sexually-transmitted disease. Sex is to blame. The root of sin. The guilt we all bear, purely by being here. Because we are the result of the act of procreation. Through this legacy, Augustine is considered the last of the Classicist thinkers, and a bridge to becoming the first of the Medieval theologians.

When Dante published ‘The Divine Comedy’ in 1321, barely ten-percent of Italians could read. The Medieval European mind had retreated from rationalism. Information was the exclusive preserve – and the power-base of the Church. They guarded that power jealously. And if the only book the illiterate majority had access to was the impenetrable Latin Bible, they ensured it could only be reached through the intermediary of the clergy. Monks sequestered in monastery ‘scriptoria’ – writing rooms, laboriously handcrafted beautiful reproductions of religious texts. Their ‘illuminated manuscripts’ were not designed simply to convey information, but to decorate the word of god with ornate calligraphy and elaborate illustration. As such, books were rare and immensely valuable possessions – in 1424 the Cambridge University library could boast no more than 122 of them, each one worth the price of a medium-sized farm. And each stage in the evolution of literacy, things we take for granted, had to be learned painfully step-by-step, from the gradual introduction of the codex – a series of folios sewn together, occasionally using human sinew for the binding material, into proto-books replacing scrolls, to seventh-century Irish monks inserting spaces between manuscript words, a convention that would only become widespread centuries later.

But it was also a world in which pleasure paved the road to Hades, and sex advice generally said ‘no!’ Contradiction, all is contradiction. Misogynistic manuals claim women use sex to drain men of their power, but also that a woman who swallows a bee will never conceive. The nervousness about female sexuality means that as soon as a respectable woman reaches the age of menstruation she’s either married off, or – forgoing the expense of dowries, she’s incarcerated in a convent. An appalling practice, but bearing in mind the forced marriages, abusive husbands, absence of birth control, and death-toll from unhygienic childbirth in the secular world outside the convent walls, maybe it’s a fate of mixed fortune? In other contradictions, Courtly literature might idealise adulterous passions and unrequited love, but the Bishop of Winchester derived a good living from brothel rents. The Medieval mindset was one in which people hurled spears at the moon during an eclipse, and believed in dog-headed men, while the monasteries enjoyed a monopoly on learning. The same church that protects its vested interests by murdering dissenters. Reading the gospels in English was a crime, punishable by death.

The trigger to escape from that Cartesian straightjacket was innocently provided by German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg’s contribution to European culture. By a new technology – called print. It was Gutenberg who formulated the key to mass communication by devising a system of moveable type as early as 1439. It’s true that various forms of woodblock printing had been used prior to this – with special claims coming from China. In fact, maybe the story starts way before that in 868AD, with the production of the world’s oldest surviving book – ‘The Diamond Sutra’, a sixteen-foot long woodblock-printed Buddhist scroll from north-west China, discovered in a sealed cave in 1907 by Aurel Stein.

This production technique, in which the relief image of an entire page has to be laboriously carved into wood, could itself be traced further back to the Han dynasty, which means prior to 220AD. The technique was picked up and used for ‘Ukiyo-e’ the copiously illustrated Japanese love-guides which flourished during Edo times – the period from 1603 to 1868 when military rulers or shogun were in power, but more specifically in Tokyo between 1650-1765. This was a ‘Floating World’ of explicitly erotic woodblock prints aimed at a visually-orientated culture – much as Manga does now? It is a form of art later admired and collected by Charles Baudelaire, Édouard Manet and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The Chinese also experiment with elements of moveable type made of hardened glue and clay, but the complexity of pictograms, compared to the relative simplicity of the easily recombined twenty-six-symbol European alphabet made its introduction easier here.

Portraits of Gutenberg vary enormously – history has annoyingly mislaid precise details of such monumental events, until no-one can be certain even what he looked like. The year he was born is also disputed. Some guess it to have been 1400, which is appropriately the year Geoffrey Chaucer died – neatly ending one hand-written era by exactly synchronising it to the dawn of a newly mechanised one. But it is known that Gutenberg was in Strasbourg where he found funding for his innovative business venture from wealthy lawyer Johann Fust, using individual characters moulded from lead, tin and antimony (the same basic components used well into the twentieth-century) to produce the first printed work in Europe – a German poem. He followed it in 1455 with ‘The Gutenberg Bible’ – of which forty-eight copies are known to survive, and hence opened the floodgates of print.

The Bible sold for roughly three times the annual wage of an average clerk, yet was still far cheaper than the old manuscript versions, and the demand for books from the flourishing universities of Europe caused the printing press to be replicated throughout the subcontinent. It wasn’t Gutenberg’s intention to undermine the authority of the church. He didn’t anticipate the Reformation. He couldn’t envisage the rise of modern science or the creation of entirely new social classes and professions. Not he, nor anyone else at the time, could have any inclination of how profound the impact of his innovation would be. He just used moveable type. That’s all. Yet by doing so he did indeed unleash all of those effects. The world’s first mass-production technology was soon echoed around the continent, and more books were published in fifty years – an estimated eight million, than had been created in the previous thousand.

Print was the world’s most explosively subversive technology. It blew apart the old hegemony forever, directly or indirectly led to wars, revolutions, and the birth of modern science. The first books to be mass-produced on a Europe-wide scale were religious texts. These were still benighted medieval days when – largely, only one book existed, the so-called ‘good book’, with its store of inflexible commandments and pre-emptive parables. Sensibly, readers and collectors soon refused to accept the Bible’s monopoly of truth, and began to treasure books for more defiantly secular reasons. Greek and Roman classics appeared in print, while scientists were also soon able to disseminate information more easily, sparking revolutions in the arts and sciences.

Also, William Shakespeare’s contemporaries could neither spell his name, or their own, consistently. With print, texts were regularised around a single reference edition – starting with the Bible, and then the rest. Language, spelling and grammar – things we take for granted, were first standardised. Marshall McLuhan even suggests that print determines the way that we think. Words build sentences, which build paragraphs. So that arguments develop sequentially, building in logical stages one following another, line-by-line, towards a full-point conclusion. Pre-literate societies, and post-literate societies do not think in that laterally structured way.

Literacy among the common people shot up, and the use of Latin declined. For the first time, an accessible Bible was translated into languages other than Latin – fifty-four men translated the Old Testament from its original Hebrew, and the New Testament from Greek, for the King James Bible (May 1611). Widespread through print replication, it was liberated from the exclusive hands of a literate priestly cabal who exercised thought-control through incomprehensible incantations. The proto-Lutherans and Protestants could distribute versions of the Bible in their own native tongue, increasingly cheaply and easily, a development that would contribute to the end of the Catholic dominance in much of northern Europe and alter the power structures of the continent forever. Now people could read the gospels themselves, and frame their own questions about why the church was not exactly living out the principles established by its founder. Tease out the contradictions and the hypocrisies. The Reformation was a direct result of spreading literacy. While the fact that political pamphlets and manifestoes could be mass-produced cheaply for the first time helped to spread radical opinions and ideas that transform society.

William Caxton was a porky middle-aged merchant from the Weald of Kent. He travelled extensively around the German kingdoms. While he was there he saw, and quickly appraised the commercial potential of the new technology. Opportunistically, he followed Gutenberg’s example by setting up a press, with Colard Mansion in Bruges in 1474 to publish his translation of the French Courtly Romance ‘The Recuyell Of The Historyes Of Troy’ by Raoul Le Fèvrés, the first known book to be printed in English. He followed it by inaugurating the first British print-‘shoppe’, setting up his own press within the precincts of Westminster Abbey in the autumn of 1476.

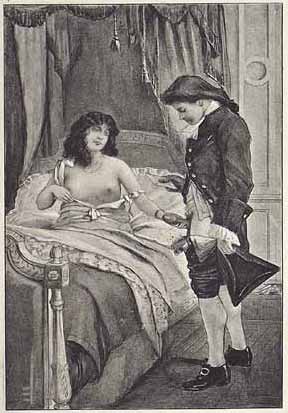

There, he began churning out copies of Thomas Mallory’s medieval bestseller ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’, and printed an edition of Chaucer’s ribald ‘Canterbury Tales’ in 1476, with its glorious portrait of Alyson, the dominant sexually-voracious ‘gap-toothed’ Wife of Bath – her dental condition supposedly signifying her hypersexuality. From there it’s not too long a step to 1668, and diarist Samuel Pepys – by turn devious, ridiculous, weak and touching, pursuing his twin passions of sex and making money, confiding his predatory intentions towards his wife’s companion to his diary, and how ‘I have a good mind to have the maidenhead of this girl.’ He confides about loitering within a certain Martib’s Bookseller, both to flirt with nubile fellow-customers and to buy the first English translation of ‘L’Ecole De Filles’ – the first recorded example of mass-market porn, already available in France since 1655. Or John Cleland’s ‘Fanny Hill: Memoirs Of A Woman Of Pleasure’ (1748), purportedly the first home-grown porn novel. Yet in truth, it goes back further than either.

The word ‘pornography’ was coined around that time, but it came from Greek roots meaning ‘writing about prostitutes’. Much further. The first dictionary definition of ‘pornography’ occurs in 1857, to neatly coincide with the first ‘Obscene Publications Act’, passed by Parliament on 25 August of the same year in an attempt to control works that tend ‘to deprave and corrupt’. But surely that definition could also be extended to include a visit to the Paris Opera on 21 October 1858 to witness the first staging of ‘Orpheus’ – introducing the world to the Can-Can, or the Paris Music-Hall of 13 March 1894, as it stages the world’s first striptease ‘Yvette Goes To Bed’? Or the years between 1895 and 1898, when ‘Metropolitan Magazine’ (1895-1911) includes generous splashes of artists’ models, dancers, art nudes, ‘Paris Beauties’, courtesans, bathing beauties, and French Music-Hall chanteuses? It even published a fully illustrated article in February 1895 about the ‘living-picture craze’ – wherein nude and semi-nude models pose as reproductions of famous or newly conceived ‘classical’ artworks.

But perhaps it’s necessary to look even further back, long long before that, with the voluptuous Salome, dancing for the head of John The Baptist… in the Bible. While the ‘Sacred and the Profane’ co-exist in ‘the Divine’ Pietro Aretino’s playful and literately subversive ‘Sonetti Lussuriosi’ (1526) with their ‘transgressive taste for the forbidden’. A conundrum most perfectly delineated by Rennaisance artist Guilio Romano’s explicitly sexual guide to sixteen copulatory positions, his series of erotic images intellectually legitimised by rediscovered evidence of ancient Roman art. It was deemed offensive only when Marcantonio Raimondi reproduced the paintings as engravings for print in an edition titled ‘I Modi’ (1524), with the addition of poetic texts by Aretino. Despite being siezed and destroyed by Papal powers it survived into a second edition which made it a European best-seller, known in Shakespeare’s London.

An ‘Index Of Forbidden Books’ was compiled as early as 1559 by Pope Paul IV, ‘The Penitential Of Theodore’ that established the Church’s code on sex. Which is, you shouldn’t do it. And if you do, you shouldn’t enjoy it. Such attempts to deny the primal lifeforce led to centuries of persecution, suffering, miserable enforced secrecy and breathtaking hypocrisy. Herein lies the real evil.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON