The enigma is that there’s no default factory setting for the human being.

As a species, as well as for the individual, we are dropped into these meat bodies running.

From the moment of birth we have an urgent need for nurturing, and for sustenance. Those things are immediate overriding imperatives. Without them we die. No options or time for choice.

We conform to a set of expectations as part of the survival strategy. Adopting behavoiral patterns through a process of osmosis. This is the tried and tested way that humans perform as a species, and specific to the time, place and cultural norms in which we happen to find ourselves. We imitate. And learn by imitation. Given the full vastness of time and geography we can count ourselves fortunate to have been ejected into the liberal tolerant inclusive welfare culture of the twenty-first century. It could have been a lot worse.

Where ethics are situational, and where morality is a human construct anyway, how are we supposed to determine right from wrong? By a slow and torturous process of dialogue and cultural conjecture.

Speech seems something integral to the human experience. A survival gimmick that enables the passing of detailed information down through generations, in order to resolve problems by comparison with the resolution of similar earlier problems. The linguistic theory propounded by Edward Sapir and developed by Benjamin Whorf, known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis suggests that language also determines world-view. Which means that the structural content of the languages of Native Americans, indigenous Australians and the Japanese will be radically different, and hence their ways of reasoning. The opposing Noam Chomsky viewpoint is that humans have an innate capacity for acquiring language, a capacity programmed into us genetically, which determines the syntactical structures and ways of putting things together. Does speech arise from a shared neural centre? Are we hardwired for speech? On the principle that speech arises from hearing it spoken, Mughal emperor Akbar is said to have experimented by having children raised in total silence by mute wetnurses, reasoning that those raised without hearing human speech would remain silent. That the children reportedly died in infancy before the experiment’s completion can either be seen as evidence of its truth, or its refutation.

That print technology enabled communications on a vaster and more impersonal scale opened up yet greater interactivity. It forms a virtual connection between minds, that links across years and continents. That print also shapes the process of thought itself was suggested by Canadian academic-theorist Marshall McLuhan, so that ‘the medium is the message.’ In print, a paragraph is constructed through a series of statements that build up into a logical whole. Which becomes the method by which we build a rational dialogue. A purely visual vocabulary would not result in the same sequential process of ideas. Humans create a technology, which then shapes subsequent humans.

We imitate and absorb the cultural norms around us. This defines our potential, and also our limitations. The way our senses are channelled and shaped by hand-to-eye coordination. There’s no operations manual on how to be human. Instead we respond to the unconscious stimulus of approval or disapproval. A process by which we learn to control our bodily functions so later we will discipline our anger. Learn not to touch ourself, or others, in those places that please most, so that later we will breed in convenient Family units. To accept the limitations we are assigned and the role to which we must conform. To accept our own worthlessness in games we are not intended to win. We are disciplined through religion so we’ll accept suffering passively and accept authority gratefully, and to love Royalty so we accept hierarchy and respect those who exploit us.

Yet because there’s no default factory setting for the human being, we can never truly know how individuals could develop without that coercive social shaping…

— 0 —

I never really saw much of my father. He was there for the conception. Then he showed up again when I was seventeen. And he immediately spirited me down to London. To Soho. A tawdry strip-club. ‘No real woman will ever be quite as exciting as your fantasy’ was the only perceptive observation of any depth he ever said to me. If we learn by imitation, beyond that revelation, he was never a factor. Whatever I’ve learned about the ways that genders interrelate, was learned elsewhere.

I’m a literary kind of person. I relate to the world through the intermediary of pages. I always have. I read. I write. Whether it is boy’s adventure comics, the escapist futures of science fiction magazines. Or the interior world of novels. So inevitably I encounter, experience and explore sex in the same virtual-reality way. Words. Images. Print. Paper. Hey, there are even packs of ‘Adult Playing Cards’ out there, the ‘Gaiety Brand’ – featuring fifty-four models with a topless Jayne Mansfield as the King of Hearts. Here is sex that takes place in an alternate continuum over-stuffed with fictional motifs where all laws of actuality are suspended, and new rules aim only at the tease of temporary suspense, and soon-come gratification.

But where do you find erotic images when it is 1959 and you are twelve years old, living in a rural satellite of Kingston-upon-Hull? Well, you find them everywhere. All you have to do is look. It’s there in my mother’s magazines. The modest underwear ads in ‘Woman’, ‘Woman’s Own’ or ‘Woman’s Realm’. Those strangely fetishistic corsets with the geodesic domes of intimidatingly massive white bras. Early sexual experiences are more intense simply because your brain is more open, more pliable, more impressionable. Which is why it can be hazardously habit-forming. Which is why it can determine the future course of your desires. When you’re young and eager, when your new sexual ‘equipment’ comes online, there’s a burning urgency to try it out. Humans have no default factory setting. Are we genetically hardwired that way, so we are biologically predestined, and have neither free-will nor choice? Or is there some lightning-flash incident in our early sexual development that is so life-changingly intense that we spend forever trying to recapture that moment, like a junkie ever-striving to relive the incandescence of that first high? Whatever, there is a need for caution, for wariness, for protection of the vulnerable until informed consent is possible, until the legislated age of maturity.

Yet it’s there in the school library too. ‘The National Geographic Magazine’ has tantalising photo-spreads of aboriginal peoples in various states of ethnic undress. Each of them subject to the closest of adolescent scrutiny. My favourite – rapidly developing into a doomed star-crossed fixation, was with a perfect Amazon rain-forest teenage girl. Continents and ocean separate us. But the open curve of her smile, the natural curve of her gleaming outwardly-pointing breasts make it no distance at all. I long for her. Ache for her. So I take her. When no-one is looking, I’m separating the page by an agonisingly gradual process of furtive discrete rips. Until she vanishes into the safe darkness of my school satchel.

But the school library also has Art books. And Great Art tends to involve nudes – as we are quick to realise from a not-altogether aesthetic point-of-view. A particular favourite is a two-page spread contrasting the Maja nude duo, for which Francisco Goya had painted two identical images of his mistress-cum-model – one naked ‘La Maja Desnuda’ (1800), the other fully clothed ‘La Maja Vestida’ (1803). What’s the story behind the two identical, but significantly different poses? One for his own delectation, the other for his client, her husband? The first, acclaimed by critic Fred Licht as ‘the first totally profane life-size female nude in western art’ (1979), the other forced upon him by a disapproving clergy? Was it the Duchess of Alba, or a streetwise knife-carrying ‘maja’ from Madrid’s Lavapiés district? This devious tease element only adds to its lure – we were seeing the secret she shared exclusively with him. She looks out of the page, directly at me. I am seduced. I’m unable to resist. I rip out the pages and sneak them into my school satchel for my now-growing collection.

Desecration of library books is no minor offence. But I’m unable to resist ripping out other art-explicit pages. It was very quiet. My satchel lies on the green/black tiled floor resting against the chair-leg on which I’m sitting. Footsteps somewhere beyond the stairwell emphasise the silence, then even they are gone. I’d been assigned, by rota, to an afternoon as School Library monitor. A Library Monitor’s duties entail sitting behind the desk and date-stamping, searching for and locating tickets and generally attending to the running of the library for whichever classes happen to be allocated to that particular room during that particular afternoon. So far, there have been three classes, and this one ‘free’ period, during which I’m alone… with the books.

There are no windows. Bookcases line the room filling its silence with words struck dumb and preserved on clean white paper. During a ‘free’ period it is the duty of the Library Monitor to replace returned books to their correct shelf. To check the shelves, the rows of titles and authors. To replace any misfiled books in accordance to alphabetic or Dewey system. After a while I transfer a few of the more obvious titles to their approximate stations, and deposit the rest at random on the shelves. Then wander around the dwarfing wall-to-wall banks of tomes. The silence intensifies. Eventually, as if by pre-determination, I found myself looking at the shelves on the wall adjacent to the library’s only door. I ease the tension from slightly bagged and decidedly grubby trouser knees with the fingers of first left, then right hand as I crouch down to see the bottom shelf. The fingers, not only the nails, are bitten down, and occasionally painful. Shoe heels gently accept the weight of buttocks.

The period is approaching its halfway point. I look at the Art books furtively. Slide one gently free from the slight pressure of its fellows. A thick book. New. Falling open to my fingers there are Classical, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Impressionist, Fauve. The classifications mean little. The only common denominator of attraction is the areas of bare skin depicted. Female skin. Classical thighs in smooth white marble photograph. Renaissance virgin breasts suckling infant messiahs. Baroque demons torturing naked heretics. Impressionist nudes. Symbolist nudes. Surrealist nudes. Breasts of lovers, of warriors, saints, whores and angels. Breasts in shadow, in half-concealing robes, in elegant poise, in a sinner’s torment, in maternal tenderness. With eclectic disregard for period or style I found endless satisfaction in the instant fantasy of the timelessness of woman. At length, feeling my satchel so close to my heels, it was the work of just a second, with the exertion of only slight pressure, to rip one of the colour plates free, and transfer it from book to bag – in anticipation of further, closer examination later. A second plate follows, as inexorable as breathing. Fingers slightly sticky with sweat, leave little ridged fingerprints on the clean white margins. Aware of a sense of detachment. Of watching myself secreting picture after picture into the school satchel. Of watching in a sense of almost disinterest the fumbling excitement of each rape, desecration, and theft.

But the two divergent selves – sensual and cerebral, were instantly re-united in a second of breath-catching noise. The library door rattled, once. Rattled twice. Someone is attempting to open the door. Fortunately, it sticks. The rattle crashes decibels, echoing around the sterile walls that are thickly-insulated with dead words and petrified ideas. Ricocheted to apocalyptical proportions, assailing the guiltily crouching boy from all directions. Guiltily crouched over a satchel that is suddenly, amazingly, crammed with artwork that has just as swiftly been transformed to pornography by the attention of the adolescent theft. There’s a face smudged up against the window set into the upper half of the door. Staring straight at the crouching petrified boy. Into, through the boy, ransacking braincells for traces of dirty thoughts and grubby impulses, rifling memory banks for smut and filth, checking each hateful idea frozen on the point of realisation… all is frozen for a long ten-year second. The door swings inwards, screaming Armageddon. A master’s head thrusts through, into the room setting up shockwaves of disturbance. ‘Mr Nelson… I’m looking for Mr Nelson. Shouldn’t he be taking a class here this period?’ Dumb. Mindless. Head-shaking.

‘I was sure he was supposed to be here. But obviously, he’s not.’ The head withdraws. The door closes. The celldoor thuds into place howling relief, echoing solitude in ripples through the charged air. Fear explodes. My hands tremble. My stomach pounds. Yet there’s a strange distant detached voice of triumph. I straighten almost too quickly. The door is closed, the footsteps recede, and they’re gone. The satchel full of guilt sprawls there, smugly accusing me. The sundered book seems blatantly thin in the clasp of my hands. The spaces where stolen pages have been must be obvious to all. I hurriedly thrust it back into the shelf, ensuring that it is correctly filed, and that its spine is at exactly the same level as its fellows. I strap the satchel up carefully, after strategically re-arranging its contents to hide – as best I can, the thick load of incriminating evidence. I return to the librarian’s desk feeling slightly giddy, almost unreal and numb. Studying columns of French verbs diligently until the bell eventually – centuries later, announces that the ‘free’ period has ended…

Joe Orton got his first-ever press write-ups not for his gender-quake plays – but for his appearances at the Magistrates court for desecrating library books. I’m lucky. I was never caught out. Fortunately, I manage to avoid the social and financial disaster that would have entailed by a close pubic whisker. But you see what I’m getting at? It isn’t that the ‘Girlie Books’, Top-Shelf Mags, or the Soft-Porn Jazz-Mags ignite unnatural desires in innocent young minds. That prurience is already there. It’s more that they kind-of meet it halfway. They intersect a need that’s already rampant with fleshy hungers desperate for satiety.

I have to tense up to buy copies of ‘Spick’ or ‘Span’ in a state of agitated determination from the man with the knowing leer in the kiosk outside Paragon Railway Station. Then walk swiftly to the deserted riverside wharf by the empty Old Town warehouses, all warped timber and the stink of stale rivermud, with the magazine thrust-hidden deep in my jacket, to sit on the metal bollard in the pale warmth of the sun, and extract it. To turn each page is a feverish new discovery. A new nude opened up to appraisal, my throat becomes drier, my mind increasingly befugged, detached from all else but their posed monochrome fascination, my blood raging. She alternately conceals, and reveals. She is totally available. Wanton. Explicit. But absolutely inaccessible. A fabrication of half-tone dots in a sexual guise that offers all, yet stays safely untouched beyond the lens. Which is – after all, as close as I can get to the feminine mystique. Masturbation, sometimes it’s a spurt of the moment thing. A Wank. A lift-Off Booster to every adolescence. But as we enter the new Space Age, it also becomes rhyming slang for ‘having a Jodrell… (Bank).’

Ex-Small Faces musician Ian ‘Mac’ McLagan recalls ‘back then, there being no nudity on television and not enough in films for my taste, just about the only place you’d see a naked woman was in ‘Health And Efficiency’, a nudist magazine, or ‘Line And Form’, a much more interesting dirty book…’ Me too. In fact I even added motion to the ‘Health And Efficiency’ photos by scissoring erotic cut-out collages for the prurient amusement of friends, made difficult for simulating penetrative sex by the determinedly down-angled flaccidity of available male members, which were – however, quite useful for paper oral sex, inserted into smiling accessible slit-mouths with a jig-a-jig motion. There were also single-sheet home-drawn sketches passed around the schoolyard, to be sniggered over on conspiratorial gaggles. Except that the images tended to peter out in vague mermaid forms where the boy doing the drawing wasn’t exactly sure what girls actually looked like… down there. John Bratby’s autobiographical glimpses in ‘Knave’ include his ‘realising then that there was a shortage of pornographic literature available to the boys in the school, I decided, when I was in the fourth or fifth form, to write some stories myself, and to sell them for a penny a read. I wrote three stories, laboriously in longhand, and made a small fortune. I did not need to advertise my wares. The chaps would talk to each other, and customers would arrive from the furthest reaches of the school building, and I wished that I had more than one copy…’

Science Fiction writer Brian Aldiss also relates – in his autobiographical ‘The Twinkling of the Eye’ (Little, Brown, 1998), how he circulated his own ‘penny-a-read’ fiction at the Buckland School, producing a form of ‘dirty SF’ and ‘dirty crime’ in which ‘screwing featured largely,’ which were often written ‘in the dormitory, under the bed-clothes, by torchlight.’ Me too, although not quite on such an industriously entrepreneurial scale. A friend in my same school year, and a near-neighbour – called John, and I came to a similar conclusion, and so decided to write our fantasies at length for each other’s consumption and furtive gratification. I duly hand him my tight ballpoint script pages of soft suckings and sensual mergings, only to be startled and confused by his own altogether more brutal and abusive take on eroticism, in which a naked girl is tied up and dragged around behind a speeding motorcycle. Both disturbed and distinctly un-aroused by this insight into his psychosexual fantasies, our literary experiment progressed no further. Presumably he was equally disappointed with my comparatively tame contribution…?

In New York, 1956, young Samuel R Delany was doing something similar. ‘Secretly in those years, I would write down my masturbation fantasies in a black loose-leaf binder I kept beneath my underwear in the tall, stained-oak bureau against the wall in my third-floor room. They had nothing to do with… any of my childhood experiences and experiments with sex. They were, rather, grandiose, homoerotic, full of kings and warriors, leather, armour, slaves, swords, and brocade, mixing the inflated language and the power fantasies of Robert E Howard (‘Conan The Conqueror’, Gnome Press, 1950) and Frank Yerby (‘The Saracen Blade’, 1952), whose books I hunted out in the local library or from the third-floor bookshelves of my Aunt Virginia’s Montclair home, with the street language of Seventh Avenue and the off-colour anecdotes collected by the brothers John and Allen Lomax in their five and six-hundred-page scholarly tomes that I found at the home of my Aunt Dorothy and my Uncle Myles – language whose erotics, in both cases, came not from the constellation of specific sexual associations but almost wholly because its ‘god-damn’, its ‘nigger’, its ‘shit’, its ‘kike’, its ‘piss’, its ‘wop’, its ‘prick’, its ‘fuck’, its ‘pussy’ was – in our house – wholly forbidden, and the specifically sexual words were, I knew, by law, forbidden to ordinary writing’ (quoted from his autobiographical ‘The Motion Of Light In Water’, Arbor House, 1988).

However, Delany discovered other elements to his handcrafted porn. ‘A fantasy I had not written out yet, or had only begun to write, would last me a long time, over several days – even a week or more. If, however, I wrote it down, filling in descriptions of place, atmosphere, thoughts, speech, clothing, accidental gestures, the whole narrative excess we think of as ‘realism’ making my written account as complete and as narrationally rich as I could, my own erotic response was much greater, the orgasm it produced was stronger, more satisfying, hugely pleasurable. But, once this has occurred, the fantasy was used up. It became just words on paper, at one with its own descriptive or aesthetic residue, but with little or no lingering erotic charge. I would have to create another…’ Inevitably his mother found the incriminating loose-leaf binder concealed beneath the underwear, and passed it on to young Delany’s pudgy Cuban therapist.

Arousal can be provoked in the most unexpected places. In Stan Barstow’s gritty northern ‘A Kind Of Loving’ (1960) his protagonist Vic Brown thumbs through a copy of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ which he’d discovered by chance on his brother-in-law’s book-shelf. ‘The next minute I’ve dropped on a bit near the end that nearly makes my hair stand up. As far as I can make out it’s a bint in bed or somewhere thinking about all the times she’s had with blokes. It knocks me sideways, it really does. I mean, I’ve seen these things what sometimes get passed on from hand to hand on mucky bits of typing paper – you know, all about the vacuum cleaner salesman who goes to a house and finds a bint in on her own – but I’ve never seen anything like this actually printed.’ His brother-in-law, David, argues that the book ‘went through several courts before free publication was sanctioned’ and that it’s ‘a masterpiece’, but that ‘I shouldn’t want your mother, for instance, to pick it up and open it where you did. She mightn’t understand.’ And his wife? ‘She hasn’t read it. She knows what it’s about, and its reputation, and she says she doesn’t feel obliged to go any further.’

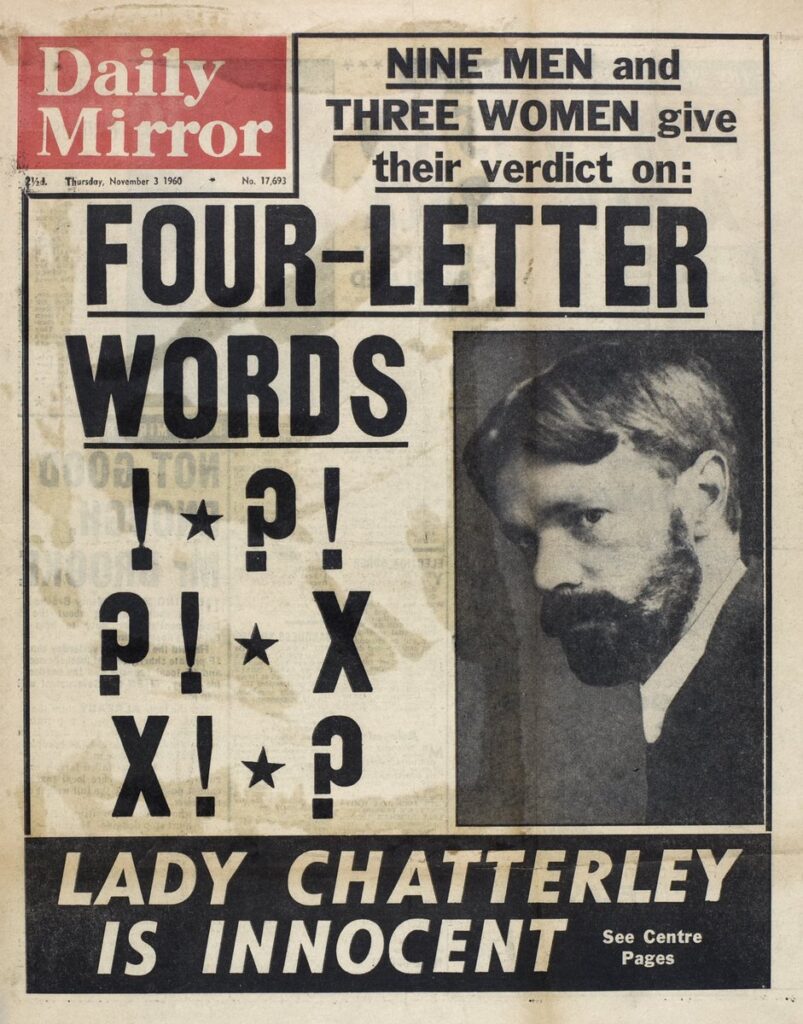

What was it the ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ trial-judge said about letting ‘your wife and servants’ read such material? To Vic, ‘Ulysses’ is not ‘magnificent’ literature. It’s just something akin to ‘mucky bits of typing paper passed on from hand-to-hand.’ To Vic, writing about sex, in no matter what context, is ‘mucky’. Author John Sutherland’s autobiography ‘Magic Moments’ (Profile, 2008) recalls the hours he spent in his 1950s adolescence locating a notorious unreadably filthy page, the rollicking obscenity of Molly Bloom in ‘Ulysses’ in Colchester Reference Library, while he and his schoolfriends obtain a copy of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ and pass it around, frenetically reading it – one-handed, in their dorm.

There existed a strange situation back then in which public libraries used the precaution of ‘block books’ – literally, wooden blocks in place of any books the librarians considered a little too risqué. The unfortunate borrower had to carry the ‘block’ to the counter and then the librarian might grudgingly provide the book from beneath their desk. No doubt with a suitably sniffy demeanor. There was, as a result, a certain habitué of libraries whose visits consist of just going around checking out the shelves looking for wooden blocks.

Walk around any shopping mall clothes store today and there are giant ad-panels of women in lingerie more explicit than the contents of the magazines we hoarded and guiltily concealed during the 1950s. Reading a cookbook doesn’t necessarily provoke a craving for food that must be satisfied. The food stays on the page. It is something abstract and disconnected. You can’t smell its aromatic quality or experience its taste. You don’t feel the need to indulge in it. But to read a sexually explicit paragraph on a page is to transfer that image-of-food onto your own physicality. Your reaction is not only cerebral, it is deeply physical. Poet W.H. Auden pointed out that the only true legal definition of pornography would be determined by first exposing an all-male jury to the questionable material, then checking their genitalia. If they were unanimously erect then the case was proven. For the object of porn is to arouse. It has a bodily function. Even when the motive behind its creation is both to be artistic as well as sexually explicit, the one continually undermines the other. Porn? Censorship? The lines are continually being drawn, redrawn, rubbed out, and re-imposed. In some circles, such publications are frowned at. I certainly frowned upon them week-after-week in the privacy of my bedroom.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON