Image: Ma Yongbo 马永波 and Ma Yongping 马永平 his poet brother, Autumn 2004

the two brothers with their umbrellas

—for Yongbo and Yongping—

撑着伞的两兄弟

——致永波与永平——

separate the falling dusk on the mountain in two.

Dusk lies, now a little smaller, in two puzzled halves;

she settles her two shadows on their dark brows.

She begins to love them and their shadowy ways,

So she begins to saturate them with darkness.

She has perfected her art at slowly ripening melancholia in men,

and their umbrellas are no defence against broodiness;

she stays on their shoulders and gently separates them

19th February 2025

Response Poetry By Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

撑着伞的两兄弟

——致永波与永平——

the two brothers with their umbrellas

—for Yongbo and Yongping—

将山间飘落的暮色一分为二。

暮色此刻蜷缩着,化作两个略小的困惑的半边;

她把两道影子安放在他们深色的眉峰上。

她开始爱上他们,和他们那带着阴影的模样,

于是她便开始用黑暗将他们渐渐浸透。

她已经炉火纯青,能让男人心中的忧郁慢慢滋长,

他们的伞根本抵挡不住这份沉思;

她停驻在他们肩头,又轻轻将他们隔开

2025年2月19日

Chinese Poetics Multilingual Magazine https://www.meipian.cn/5g6rlm36?share_depth=1

“This is a poem Helen wrote for a photo of me and my late elder brother, the poet Ma Yongping. At that time (the autumn of 2004), I had just come from Harbin to teach in Nanjing. My elder brother came to Nanjing from Yinchuan to join me the following summer and worked as a night watchman in the student dormitory of our university for ten years. This photo was probably taken when we visited Buddha’s Hand Lake on the north bank of the Yangtze River. I was about 46 years old then, and my elder brother was six years older than me. After I moved to Nanjing, my two elder brothers came to me one after another, and sometimes my elder sister also came from our hometown to stay in Nanjing for a while. Our parents passed away in the 1990s, so there are only four of us siblings in our original family. Occasional reunions became a great source of happiness for us.

I am grateful to Helen for her poem, she captured the essence of us brothers, especially my innate melancholic disposition. She also deeply understands the blow I suffered from losing my elder brother, whom I had relied on, and we had supported each other. During the 17 years I taught in Nanjing, my wife and son remained in Harbin, and Yongping was also alone. After he started writing poetry in 2008, he understood my situation and mental state very well. We often traveled to scenic spots together, read and talked about poetry. Sometimes, after my classes, I would drop by the student dormitory area where he was on night duty to chat with him. Then, he would walk south in the late night, taking forty minutes to return to his tattered rental shed in the urban village, while I would walk north, slowly heading back to my own home at the foot of Purple Mountain.”

Ma Yongbo, September 2025

Image: Helen Pletts, Cambridge, 2025

Grain-Transport River: A Visit to My Elder Brother, Unmet

运粮河:访家兄不遇

I have never been here before. As a canal,

it is unremarkable—a dredged waterway

winding its way to the Outer Qinhuai River.

It no longer carries the task of transporting grain

from the eastern suburbs into the city.

Those who once stood along its banks have all vanished,

and nothing new comes flowing

from the river’s source.

Along the way, the golden of rapeseed flowers divides the fields,

someone patiently applies green paint to the railings,

covering the rust as if covering his own eyes.

Why love the world, if the world

is merely a rusted fence in spring

enclosing a pile of grey wood?

Someone loves them without letting them know,

otherwise that love would degenerate.

I have never been here before, yet here lives

a relative of mine. In the morning or evening,

he practices martial arts by the river,

gazing at the water without moving for a long time.

Only by travelling back to the Ming Dynasty

would you have the chance to see him—

his hair tied, his face gaunt, wearing a cyan robe, saying nothing.

Then, perhaps you could stand beneath a willow in the distance

and quietly listen as the river’s voice rises in successive waves,

the mighty spring breeze slowly filling your clothes.

2016.3.19

Response Poetry by Ma Yongbo 马永波

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

Grain-Transport River: A Visit to My Elder Brother, Unmet

运粮河:访家兄不遇

我没有来过这里,作为运河

它再普通不过了,经过疏浚的河道

曲折通向外秦淮河

它不再担负从城东运粮进城的任务

曾经站在河边的人都已消失不见

也没有什么新鲜的事物

从河的源头而来

沿途,油菜花的黄金分割田野

有人把绿漆耐心地刷在栏杆上

掩盖住铁锈,就像掩住自己的眼神

为什么要爱世界,如果世界

只是春天生锈的栅栏

围着一堆灰色的木头

有人在爱着他们,不让他们知道

否则这爱就会退化

我没有来过这里,这里住着

我的一个亲人,他或早晨或傍晚

会在河边打拳,望着河水久久不动

你回到明代,才有机会看见他

束发青袍,面容清癯,不说话

那时,你或许可以站在远处的柳树下

悄悄听河水的声音一浪浪高起来

春风浩荡,慢慢涨满你们的衣服

2016.3.19

My Elder Brother Yongping, in My Eyes and Heart

1

What more can be said? Everyone has been young once, everyone has longed for the future with burning hope, only to unknowingly become the very version of themselves they least wanted to see. Is there any use in lamenting the ruthless passage of time? Knowing it is useless, we still write it down. Knowing that even writing it down will eventually be scattered by the wind, we still write it down—just as we know we cannot resist the manipulations of fate’s great hand, yet still, as my elder brother wrote in his poems, generation after generation faces that invisible fate with both fear and courage.

Even the most ordinary person has a story that belongs to them alone. My understanding of my brother is limited to two periods: my childhood and adolescence, and the ten years in the new century (2008–2017) when we relied on each other as brothers. After starting our own careers and families, we lived independently, making it hard to say we truly knew each other. Yet in the last twelve years of his life, for ten of them, I was the most “authoritative” witness to both his daily life and inner world. We spent our days together, traveled side by side, found joy in poetry, carving and polishing each other’s words. These shared experiences allowed me to truly understand my elder brother. The instinctive closeness born of familial blood ties, the hardships of wandering together and supporting each other, and especially the deep connection we forged once he started writing poetry—all of this brought a profound tenderness between us.

Once my brother entered the depths of poetry, he also understood how I had stumbled my way through the past few decades. He wholeheartedly supported every poetry-related endeavour I led, always encouraging me to persevere. He also saw firsthand how dark the literary world could be—a darkness so terrifying that outsiders could never fully comprehend it. There was no beauty in it, not a trace. The only beauty lay within the act of writing itself. But the moment one stepped beyond the writing process, the world was shrouded in foul smoke, suffocating any decent person. How did Chinese society become a place where goodness could not survive? Every field, without exception, is the same.

Yongping was not one to reject people or things outright—only when his inner peace was disturbed would he choose to withdraw. In his own poetry, he wrote that he lived “outside of life,” and perhaps an outsider’s perspective best describes his relationship with the world. But when did this begin, and why? What kind of power and game mechanism forces some people to live on the margins—watching, but never truly living?

2

My eldest brother once had a very “proper” life. How did he slip, step by step, from a normal existence into a quagmire of suffering from which no effort could rescue him? This is something worth deep reflection. His story reflects a most truthful cross-section of society.

After graduating from high school, my brother was sent to the countryside of Xicheng Township, Keshan County, as part of the Down to the Countryside Movement. There, he stayed with Grandpa Zheng, an old comrade-in-arms of my father. Our families had a close bond, and my childhood experience of the countryside mostly came from visiting Grandpa Zheng’s home. I remember the warm, pungent smell of chicken droppings in the muddy yard, the crooked wooden fence bleached gray by wind and rain, the blackened thatch on the roof, the sunlight streaming onto the earthen kang, the red quilt covers, the baby cucumbers in the backyard garden, and the deep, pure fragrance from the stems of half-green, half-red tomatoes.

Later, Yongping returned to the city and joined the army, serving as a truck driver in Dalian. At that time, I was in third grade through middle school—those were my years of diligent study. In our correspondence, I promised my brother—who was half a mentor to me—that I would master both martial arts and fine arts. That was my aspiration then; I had never imagined becoming a poet. In elementary school, Yongping bought me watercolour and gouache paints. Every morning, I would carry a small bowl of water, climb onto the warehouse roof to paint clouds and sunrises, or sketch anyone I could find in the alleyways, refusing to let them move.

After leaving the army, Yongping returned home and worked as a cashier or office clerk at a photo studio and a tobacco and liquor company—jobs that were easy and enjoyable. His family life was also perfectly normal. But in the 1990s, his workplace dissolved, and he had to buy out his work years and fend for himself,his hardships began. From then the warmth of family life never visited him again.

After losing his job, Yongping was forced to leave home alone and work wherever he could, enduring endless hardships—raising silkworms in the mountains, digging sand in Changchun, loading and unloading scrap metal in Harbin, planting trees in Yinchuan, and working as a dormitory attendant in Nanjing. Born in 1958, he was a product of his era, a generation doomed to suffering: unable to learn anything in school, sent to the countryside as a rusticated youth, laid off from work. He encountered every misfortune possible. A life of few desires and little joy—one could even say, a life of deep suffering—he was a representative figure of his time. Yongping once said that the only truly good years he had were in childhood. In truth, we were not much different. If we think carefully, has anyone ever lived truly free from worry? Has anyone truly lived for themselves? Even without the hardships imposed by the world, the mere existence of our own bodies, with their illnesses and inevitable aging, is already burden enough.

Where is the ocean of life?

Raising silkworms turned out to be a futile endeavor that did nothing to change his circumstances. Based on Yongping’s account, I wrote Listening to My Brother Talk About Raising Tussah Silkworms, which was later included in my essay collection Snow on the Hedge, published by The Commercial Press.

In his forties,Yongping went to Changchun to dig sand. My second brother Yonggang went to visit him and saw the deep pits—so dangerous that even some young men in their twenties fainted inside—yet my eldest brother endured, thanks to his martial arts training. The food was terrible, consisting almost entirely of steamed buns and cabbage soup. My second brother took him to a restaurant and ordered several meat dishes, which Yongping devoured hungrily. This reminded me of the two years after I graduated from university, around the late 1980s. One time, Yongping passed through Harbin on his way back from a training program in Zhengzhou. He was so thin it was alarming. When I asked him what he wanted to eat, he simply said, “Meat.” At a small restaurant near the vehicle factory, I ordered at least three meat dishes—Yu-Shiang shredded pork, Guo Bao pork, and others. Yongping finished them all; I barely ate anything.

At the start of the new century, I brought Yongping back from Changchun to Harbin, where he worked in a boiler factory, unloading scrap metal and coal briquettes. He lived at the factory. Those years were also a turning point in my own life. Yongping often came to my house to watch movies, and he loved martial arts films—as expected of a martial artist. He also had a childlike pride at times. When we were young and practicing martial arts together, one day we saw a group of men practicing with spears on the street. Yongping scoffed, saying, “Three punches and two kicks would be enough to deal with them.”

He was known for his strong fists in our county. Sometimes, local thugs or others with some fighting skills would challenge him. I personally witnessed several such incidents, they were no match for my eldest brother and were beaten so badly that they fled in disgrace. I recorded these fights in my poetry. In reality, he rarely fought—he was an honest man, only resorting to violence when absolutely necessary, or to protect my second brother and me.

During his five or six years at the boiler factory, the work was neither too heavy nor too light, and he finally had a chance to recover. When he first returned from digging sand in Changchun, his face was sunken. But in those years, his face filled out again. My wife and her colleagues treated him very well—perhaps being near his younger brother and sister-in-law lessened his sense of drifting. Every year, he could only return to Keshan during the Spring Festival to reunite with his wife and daughter. Despite his meagre income, he supported his daughter Xiaoling in learning makeup artistry and fulfilled his responsibilities as the head of the family.

Before leaving for home, he always came to say goodbye. I once wrote a poem about watching his small, solitary figure disappear into the night as he walked back to his dormitory—an image that filled me with sorrow.

Then one day, while loading cargo, Yongping’s left pinky finger was crushed by a truck panel. My wife only told me after the surgery. She said Yongping’s face turned pale from the pain but didn’t utter a sound—just sweat pouring from his forehead. “Ten fingers connected to the heart”—even a martial artist feels pain. The legendary “scraping poison from the bone” is either a myth or an extreme rarity.

My brother was left-handed; his left fist was stronger than his right. Even in the few times he had to fight, he avoided using his left hand for fear of seriously injuring someone. Left-handedness was inconvenient, inherited from our mother. When he was a child, our mother often beat him, trying to correct it, but the more she hit him, the more stubbornly left-handed he became. He even picked up smoking early on, influenced by our mother. He once said that as a child, he thought our mother looked elegant when she smoked.

Of the four children, my mother loved my eldest brother Yongping the most. He was her best helper—always quietly getting things done: carrying coal, storing vegetables for winter, dismantling and repairing the kang bed, (kang – a bed found in northern Chinese homes modelled of earthen clay or brick and heated from underneath) chopping wood, taking out the trash, breaking ice in the sewage pit during winter, digging cellars, carrying water. He did it all, often alongside our father. Our father, despite being a mid-ranking officer, was a hands-off figure at home. He would get frustrated whenever he had to do housework, sometimes throwing down the tools in irritation. I inherited this trait—mundane tasks annoy me endlessly unless I take them on voluntarily. If forced, I have no patience whatsoever.

After his injury, Yongping couldn’t do heavy labour anymore. Life had to go on. Around 2003, he went to Yinchuan to seek work with our second brother. My second brother rented him a house and prepared a stall for selling grilled sausages and corn. However, due to his personality, he wasn’t suited for small business, so he went up the mountain to plant trees for others. Later, for personal reasons, the second brother moved his family to Dongying, Shandong, to sell steamed buns. Yongping stayed alone in Yinchuan to make a living. During those two years, we lost contact with him, and the second brother posted a missing person notice. We almost had to call the police to report him missing. Just when we were desperate, Yongping’s phone call came through from Harbin. It turned out that he had been in the mountains, where there was no signal, and he couldn’t use his phone. At that time, his monthly salary was only five hundred yuan, and I figured he couldn’t afford a phone. The period is mentioned in his poem Dreams on Helan Mountain.

Yongping liked Yinchuan very much. He said it was warm in winter and cool in summer, like the Jiangnan region of the northwest. The lamb was delicious, and he told me that we should go back there together sometime. I’ve never been to Yinchuan, but if I go in the future, I imagine my feelings will be very complicated. Both of my brothers lived there for many years. One of Yongping’s many selves still resides in that city, but I can no longer find him. Though Yongping has passed away, in my heart, he is still alive—he simply no longer meets with me, no longer contacts me, but quietly continues practicing his Qi. I can no longer disturb him.

3

The harm of being adrift without a home is immense. I only truly understood the suffering of a homeless wanderer in 2007, when I left my hometown and traveled alone to the south. The bitterness, the hardships, the frost in my hair—these are feelings difficult to comprehend without experiencing them firsthand.

In the spring of 2008, my second brother and his family came from Dongying to Nanjing to reunite with me. The two of us then contacted Yongping, who was far away in Yinchuan, and invited him to come to Nanjing as well. The brothers were together again. In early July, our eldest brother Yongping arrived in Nanjing. My second brother and I went to pick him up at the station. From a distance, we saw him emerging from the passageway—his face ashen, his body so thin he was almost unrecognisable. The once-cute little tiger teeth from childhood had grown too long. My second brother was also shocked. After only a few years apart, not only had he aged, but he also looked entirely different.

As a child, I listened to my eldest brother’s instructions the most. I practiced boxing with him. There were things only he could persuade me to do. But as we grew older, I realised that even my eldest brother is just an ordinary person. His small figure among the crowd was inconspicuous, and I felt a quiet sense of disappointment.

The southern heat was unbearable. When Yongping first arrived, he stayed with me. A few times, when he went downstairs to go to work, he got lost and walked in the wrong direction, heading north out of the university campus instead of south to the student dormitories. Well, at least he finally found his way! He often said, “The more you fear something in life, the more it comes to you.” He dreaded staying up all night, yet his dormitory security job had a rotating three-shift schedule. The early shift was fine, the middle shift—where he returned home at midnight—was still manageable. But the night shift, from 10:30 p.m. to 7 or 8 a.m., was unbearable. He had to patrol multiple dormitory buildings, climbing the floors repeatedly to check in electronically. It was sheer torment for those meagre wages. He started at 850 yuan per month, and after several years, it only increased to just over a thousand.

In 2009, my son Ma Yuan came to Nanjing for university, but in reality, it was to keep me company—his father, who lacked survival skills. Yongping then moved out and rented a place on his own. Some people live in a state of homelessness both physically and spiritually. Yongping expressed this deeply in his poem Ant in the Wind:

Ant in the Wind

It cannot find the way home or the way out.

Its nest is buried under dust.

The wind has snapped its two antennae,

like broken twigs.

It turns cautiously in circles on the ground,

or races back and forth on a fallen green leaf,

running from one side to the other.

And the broken antennae, like two antennas,

sway as it runs, searching.

The wind blows from afar,

and still, it paces on that leaf,

anxiously circling,

desperately seeking the way home,

as if trying to return before twilight fades.

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

Yongping lived in two places: Zhengjiaying and Jiangjiajie. He rented a tiny, makeshift shack in an urban village for about a hundred yuan a month. Inside, there was barely enough space for a bed, a rice cooker, and a few scattered belongings. The door was just a thin board—one kick, and it would break. I often asked if he was afraid, but perhaps because of his martial arts training since childhood, his vigilance was high, and he feared nothing. His righteousness kept all evil at bay. I suggested he wedge a chair against the door at night, but he dismissed the idea.

After his middle shift, he would walk nearly an hour home in the dead of night. I asked him to carry a hammer that Ma Yuan had made during his metalworking class for self-defence, but he refused. He said, “If anyone comes within ten meters of me, I can sense their intentions instantly.”

Money can solve many practical problems. During these moments, I felt immense guilt—having devoted my entire life to poetry, I had created no wealth to help my loved ones. A few times, I showed up unannounced at his place. Yongping was overjoyed, and we cooked Thai rice and braised tofu in that tiny, cramped room. But once, when our sister insisted on thoroughly cleaning his place, he got angry and refused. Sometimes, a person’s psychological state is incomprehensible to others.

Perhaps martial artists are more sensitive to their surroundings. Yongping was extremely particular about his bed—he couldn’t sleep at my place or my second brother’s home. So, even on New Year’s Eve, after our reunion dinner, he would return to his little shack in the middle of the night. Insomnia meant he couldn’t practice Qi, and his exhausting job made his life even harder.

Every summer, when I visited my family in Harbin, I left my home to Yongping. I jokingly posted on WeChat, “The Ma household is now guarded by a martial arts master—free challengers welcome.”My home was also a barebones place, filled with books but little else. At least it had air conditioning and a shower. Yongping said it was like heaven compared to his place. Yet even there, it took him several days to adjust before he could sleep. One year, he simply couldn’t rest on the bed—perhaps fearing he’d roll over in his sleep and start doing somersaults? Instead, he ignored two large beds and camped out on the floor in the living room for over forty days.

Ultimately, a person needs “a room of one’s own.” Even if it has no view, even if it’s shabby—golden mansions and silver palaces are nothing compared to one’s own little nest.

Yongping and I shared many interests. We loved aimless wandering. Ordinary folks like us, with our buzzed haircuts, had nothing better to do than watch the bustling world from the sidelines. Wealth and prosperity had nothing to do with us. Had I not been relentless in my pursuit of education—crossing disciplines at forty to earn a PhD in literary theory—I might have ended up like my eldest brother, struggling to survive after being laid off. We often wandered together. He loved photography and nature. I took him to every scenic spot in Nanjing, to Suzhou, where poet Xiao Hai hosted us, to Hangzhou, where poets Ren Xuan and Tu Guowen welcomed us, to the Chenghuang Temple and Changxing Island in Shanghai, to Xi’an, and to Huai’an, where woman poet Mel treated us like family. We never made it to Yangzhou or Taiyuan. Yongping admired Shanxi poets like Zhao Zeting, Tang Jin, Fei Mo, Xue Zhenhai, Zhao Shuyi, and Han Yuguang, and he longed to meet them. It’s a regret I couldn’t fulfil—I had neither the time nor the opportunity.

A person needs dignity. Whether others respect you doesn’t matter—life isn’t about earning respect. My eldest brother had an unyielding sense of pride. He never asked for help, enduring hardships alone. I finally found an excuse to give him ten thousand yuan, and he used it to buy a Huawei smartphone, which he loved. He also got his teeth fixed. But the remainder? He secretly gave it back to me at Ma Yuan’s wedding, refusing to accept it no matter what. It was heartbreaking—he was thinking of me, knowing my meagre salary was hard-earned. But his stubborn refusal also frustrated me. The Ma family temperament runs deep.

Giving is generosity, receiving is grace. I believe May Sarton’s words had a point.

I named both my two brother’s children—Yanling and Yanchao. Our family has tall genes: my eldest sister 174 cm, my second brother 182 cm, and I am 186 or 188 cm. Only Yongping was just over 170 cm. He always said malnutrition in childhood stunted his growth. My nephew and Ma Yuan are nearly 190 cm. Standing next to us, Yongping suddenly looked like a child. In “When I Was a Little Boy”, he expressed his regret over his height…

When I Was a Little Boy

I often hid in the willow thicket by the small river,

hoping to grow tall and strong like an ox.

But I thought oxen were a bit clumsy, though sturdy.

When I grew up, I was greatly disappointed—

neither tall nor strong, even a bit small.

For a long time, I brooded over my height,

but there was nothing I could do but accept it.

When I was a little boy,

I never played with boys younger than me.

I thought they were too childish, too ridiculous—

playing house, hopscotch, or jacks with girls.

That was boring, no fun at all.

I only played with older boys,

or at least those my age.

We staged battles, swam in the big river, caught fish,

hid in the willow thicket, climbed trees for bird nests,

set traps for sparrows, played marbles,

or used slingshots to hunt all kinds of birds.

Sometimes, we even secretly shattered people’s windows—

especially when the summer birds came.

There was a tiny bird, light green all over,

but we didn’t know its name.

Later, we gave it a loud nickname—

“Blind Brag.” It didn’t sound great, but it was fitting.

It hopped from branch to branch

on hawthorn trees covered in white and red blossoms.

When I was a little boy,

we had so many fun things to do.

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

Yongping has only one daughter, so he cherished his two brother’s two sons deeply.These two nephews of his later had sons of their own, which brought my eldest brother even more joy.This was a great comfort in his life. Such a traditional view isn’t necessarily conservative or feudal—it’s simply a natural bond of blood. Continuing the family line is a great human hope, even in the face of the world’s end.

At the end of 2007, Yongping and I went to Shanghai several times. He planned to retire and train on Changxing Island, saying the northern winters were too cold for his practice. Once, at Shanghai Hongqiao Station, we unexpectedly ran into Ma Yuan, who was just passing through on a business trip. The three of us happily spent two brief hours in that vast transportation hub.

Yongping never had a son of his own, so he regarded Ma Yuan as his own child. That day, he wrote a touching poem—

In the Hall of Shanghai Hongqiao Railway Station

I search for my tall and sturdy child.

In the blink of an eye, he is lost among countless strangers.

I meet my nephew, Ma Yuan,

by chance in the hall of Shanghai Hongqiao Railway Station.

He is heading to Hangzhou, where his life awaits.

We have our destinations.

We meet in haste, and part just as quickly.

I fall into brief joy, and a greater loss.

I look into his eyes and ask,

“When will I see my grandnephew?”

He says: “That’s hard to say!”

Then I reply: “You must try!”

Now I am sixty,

suddenly at the age when my father passed.

Shanghai Hongqiao Railway Station, October 26, 2017

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

4

Yongping lived an extremely simple life—both by choice and out of necessity. He could only save from what he ate. Aside from smoking low-quality cigarettes, perhaps only his practice brought him joy or peace. Last spring, I gave him a pack of He Tian Xia, a very expensive cigarette brand,and within two days, he had used it up, I was a bit surprised, but really, that was the right way—when you have something, enjoy it while you can.

Whenever I had a dinner gathering, I always invited Yongping. In the early days, he would usually join me, but later, he felt that even poets were unbearably mundane, so he stopped coming. He once said that only when he was with me could he have a decent meal. His teeth weren’t good, so he had trouble chewing. I would always make sure to order a few softer dishes first. One time, when we went to the cafeteria together, I was shocked to see that he ate only one dish.

Poverty is a demon—it never stops mocking and humiliating us. Fortunately, in the year and a half after his retirement, when he reunited with his daughter in Keshan county, he had some good days. His daughter, Xiaoling, cooked a lot of delicious food for him, and he said he was stuffed and even gained weight. That comforted me. But why only a year and a half of good days? At the end of 2017, Yongping returned home, but he immediately fell ill for a month and a half due to the climate. Then, he had to take care of our sister, Xiuqin, who had cancer. For a long time, he slept on her couch to make it easier to look after her. He stayed with her until she passed away on June 27, 2018. For twenty-five days straight, he barely slept. Who could endure that? His blood pressure skyrocketed. I once suffered from a week of insomnia—despite having no work to do, I nearly collapsed. Compared to my eldest brother, I was nothing—he had an unimaginable capacity for enduring the hardship.

I didn’t see him during the summer or winter of 2018. He texted me, saying he needed time to recover. I believe that his sudden cerebral hemorrhage was likely linked to his blood pressure. Actually his truly peaceful and good days were only that brief period after caring for our sister—just a year and a half. So short.

In the spring of 2019, perhaps after recovering his health, he grew restless. In a WeChat message, he wrote:

“Ever since returning from Nanjing, I can no longer go accompany my younger brother, Yongbo. I feel guilty about it! Life is filled with too many helpless moments, too many choices we cannot make. Perhaps this is just how life is. Or perhaps, life was never meant to be this way.”

On April 19, Yongping returned to Nanjing to see me. During his visit, he traveled with Yuanfan and me to Xi’an to attend our alma mater’s alumni literary association’s annual gathering. There, he reunited with my old friends—his friends too—Tong Xiaofeng and Wang Jianmin. He especially liked Jianmin’s son, and they even planned a trip to Qinghai together for the summer.

During his days in Nanjing, I was busy teaching, and he wandered around aimlessly. On June 4, while in the Purple Mountain, he wrote what would become his last poem, “The Road in the Mountains”.

The Road in the Mountains

I like mountains

Of course, not this mountain

But another mountain

Yet I don’t want to tell you its name

I like every road in the mountains

Every breeze and rain sound in the green leaves, and the flickering sunlight

Every road in those mountains has been walked by many

But there are also roads where no one has walked

I like mountains

But I especially love the moonlight in the mountain nights

But tonight there is no moon

The night sky is pitch black

The people of the mountain should be down in the valley

In the blink of an eye, they vanish on the roads of the mountains

But those who remain are still there

At this moment, I must descend

Along the silent mountain roads and lights

June 4, 2019, in the heart of Purple Mountain. This is Yongping’s last poem.

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

On June 21, the two of us flew back to Harbin—his only time ever flying in his life. He stayed there for a few days before returning to Keshan to be with his daughter. After more than twenty years of separation, father and daughter finally spoke out all their inner feelings, reaching the deepest understanding and emotional closeness of their lives in the last two years of his life. This, too, brings me comfort. People need to communicate in time, need to be together—family or not.

Some people are born with a deep pursuit of life’s meaning and an insatiable curiosity for its mysteries. My family is like that—Yongping practiced Qi, Xiaoling followed Buddhism, and I wear the mantle of Jesus Christ. Though our paths differ, the inner drive is the same—a quest for spiritual purity and the redemption of the soul. Most people do not share this pursuit, never making it their life’s priority.

Yongping did not live a long life. Was it a regret? It depends on how you see it. Sixty-two years—at least two years more than our father had. We had hoped he might live to seventy-five, but beyond that, we dared not dream. Yet, life isn’t about length—if you complete what you must, that is enough. Even if people survive a hundred years, they will still return to dust. Yongping lived sincerely and fully, with discipline and clarity—he practiced his Qi, he wrote his poetry. That is enough. No regrets. That’s all there is to it.

To recall past happiness in times of pain, and to recall past pain in times of happiness—how different those feelings are.

January 10, 2020—what kind of day was it? I don’t want to say anymore. That bitter, bleak, smog-filled dawn and dusk in a northern county town—when I saw my beloved eldest brother for the last time, I spoke to him:

“Eldest brother, how could something this terrible have happened to you?”

There was no reply. Death—it is too real.

Now, everything is over. No more hunger that burns like fire, as in his poem Sister, Rope, and Potatoes. No more pain. No more poverty stripping dignity from those who deserve dignity. No more tears. No more sorrow.

Everything has ended—so completely, so tangibly.

2:40 AM – 8:00 PM, Ice City, February 3, 2020

Revised on the morning of February 4.

The Chinese version link:

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/HC3S2DjeDlQhbzTgbNArrA

我眼中和心中的大哥永平

1

还能说些什么呢?每个人都曾经年轻过,都曾有过对未来热切的向往,却不知不觉活成了自己最不想看到的那个样子。叹息岁月流逝的无情有用吗?明知没用,却要写下来,明知写下来也终会随风而散,却还是要写下来,就像明知命运巨掌的拨弄无法抵挡,却还是要像大哥诗中所写,一代代人恐惧又勇敢地迎向那无形的命运。

再平凡不过的人,也有只属于自己的故事。我对大哥的了解,仅限于两个时段,我中小学期间,新世纪我们兄弟相依为命的十年(2008–2017),工作成家后各自独立生活,很难说有真实的了解,大哥生命最后十二年中有十年,我是他生活和内心最“权威”的见证人,朝夕相处,并肩同游,以诗为乐,如切如琢,这些共同的经验让我真正理解了自己的长兄。出自血脉亲情的本能的亲近,共同漂泊在外互为股肱的艰难时日,尤其大哥开始写诗之后,我们彼此的理解达到了最深切处,血缘和这深切的理解带来的是彼此的疼惜。

大哥自己进入诗歌内部,也更能明白我这几十年是怎么跟头把式地走过来的,对于我牵头的所有诗歌行动,大哥都全力支持,也总是鼓励我坚持到底。他也真实地了解到了文坛有多么黑暗,那是任何外人难明究竟的暗黑恐怖,绝无一丝一毫的美好可言,美好的仅仅是在写作本身之中,从写作过程中出来,一片乌烟瘴气,善良人根本喘不过气来。中国社会怎么就成了一个容不下善良存活的社会呢,各个领域莫不如此,无一例外。

永平一般不以拒绝的姿态对待人和事,例外的仅仅是当他的心灵平静被扰乱时才会回避,他自己在诗里说自己生活在“生活之外”,旁观者更适合描述他与生活和人世的关系。从什么时候起,又是什么原因,让一个人在边缘之外生活?是什么样的权力和游戏机制导致有些人只能干瞪眼地活着,被生活着?

2

大哥曾有过非常“正规”的生活。他是怎么从正常生活中一步步滑跌进怎么努力挣扎都没用的苦难泥淖中的,这不能不让人深思。这里反映了一个社会最真实的横断面。

高中毕业后,大哥在克山县西城乡下乡插队,那里有父亲的老战友郑大爷,和我家是通家之好,小时候我的乡村经验主要就来自于去郑大爷家“下屯”,泥泞的院子里鸡粪热烘烘的气味和泥上的爪印,里拉歪斜的风吹雨打变得灰白的木头栅栏,屋顶上发黑的茅草,土炕上的阳光和红色的炕衾,屋后园子里的小黄瓜妞,半青半红的柿子果蒂凹处格外浓烈而纯正的味道……

大哥后来后回城参军,在大连当汽车兵。那时我应该是小学三年级到初中二年级之间,那正是我勤学苦练的几年,在我们的通信中,我还向等于我半个师傅的大哥保证要学好武美二术,那时的理想就是这个,从没想到会成为诗人。小学时,大哥给买了水彩和水粉颜料,我就每天早上端着小碗盛着水,蹲仓房顶上画云画日出,又在胡同里逮着谁就不让动,给画素描。

大哥退伍后回到家乡,在照相馆和烟酒公司工作,做的是出纳还是什么办公室职员,反正工作轻松愉快,家庭生活也非常正常。90年代单位解体,买断工龄,自谋生计,大哥的苦日子就开始了。家庭的温暖就再也没有光顾过他。

失业后,大哥被迫孤身外出,到处打工,吃尽了苦头,山上养蚕,长春挖沙子,哈尔滨装卸废铁,银川种树,南京做学生宿舍值班员。大哥生于1958年,时代使然,他那代人命运悲惨,上学时学不到东西,下乡插队,下岗失业,可以说坏事全赶上了。寡欲少欢,甚至可以说苦难深重的一生,是具有代表性的时代缩影。大哥曾说,这辈子也就童年时有过几年好日子,其实我们也差不多,仔细想想,有谁真正无忧无虑过,真正为自己活过?即便没有外界强加给我们的苦难,光是这身体本身,其病痛和衰老带来的种种,也够一说的了。

生活的海洋在哪里?

养蚕也是白折腾,没能改变生活处境,我曾根据大哥的讲述,写下了《听大哥说养柞蚕》,收在我商务版的随笔集《树篱上的雪》里边。后来大概四十岁左右,大哥在长春挖沙子。二哥去看他,发现那深坑,有的二十来岁小年青都晕倒在里边,大哥还能挺住,这是多亏了练武打下的底子。吃的特别差,几乎就是馒头和白菜汤,二哥领他去饭店,要了好几个肉菜,大哥咔咔都造了,这让我想起我大学毕业那两年,大概80年代末,大哥有一次从郑州培训功法回来路过哈尔滨,瘦得够呛,我问他想吃啥,他说来肉吧,我俩在车辆厂附近小店,给他点了应该是至少三种肉菜,记得有鱼香肉丝、锅包肉,也是咔咔全造了,我基本就没动。

新世纪初,大哥被我从长春弄回到哈尔滨,在锅炉厂型煤厂装卸废铁等,他那时住在厂里,那几年也是我的命运发生重大转折的时期。大哥常来我家看录像,他最喜欢武侠片,练武的人嘛。大哥也有其孩子气的一面,有时很是骄傲,我小学时一起打拳的那几年,有一次我俩路上走,看见有几个人拿着扎枪在那里也在练武,大哥不屑地说,三拳两脚就能把他们打发了。大哥会武且拳头很硬,在县里是闻名的,有时会有小流氓和其他有两下子的来挑战挑衅,我亲见数次,都被大哥消得狼狈逃窜。看大哥打仗的趣事我基本都记录在我的诗里了,其实他也没打过几次,是个典型的老实人,除非逼不得已,或是为了保护我和二哥。

在锅炉厂那五六年,活不轻不重,大哥总算缓过点乏来。从长春挖沙子回来,瘦得脸都瘪了。那几年缓得脸上也圆润了许多,拙荆及其单位同事对大哥都非常好,也许因为是在自己弟弟弟妹身边,漂泊感有所减轻吧。那几年大哥年年要到春节才能回克山与妻女团聚,用非常菲薄的收入养家,支持小玲学化妆手艺,尽到了一家之主的责任。大哥回家前总会来和我道个别,我曾用诗表达过他深夜一个人走回工厂宿舍,我从窗户望着他走远的小小背影时的那种凄凉之感。

后来有一次装车,大哥的左手小手指被刹厢板轧断了,手术做完,拙荆才敢告诉我,说大哥疼得脸煞白,可就是一声不吭,满脑门都是汗,所谓十指连心,即便是习武者,疼也是一样的,刮骨疗毒那是传说或特例。大哥是左撇子,左拳力道大过右拳,所以不多的几次出手,他都避免出左拳,怕给人真打坏喽。这左撇子吃饭碍事,遗传自我们母亲,母亲小时候因此没少揍他,就想把他纠正过来,可越揍越左,甚至大哥很早就学会了抽烟,一辈子抽烟成了主要乐趣之一,也是受母亲影响,大哥说小时候看妈抽烟,就觉得那样挺美。

四个孩子中,母亲最疼大哥,一个帮妈干活的好帮手,总是不声不响就把活干了,拉煤,储秋菜,扒炕,劈柴,倒垃圾,冬天刨污水池的冰,挖菜窖,挑水,总之基本都是大哥干,或是和父亲一起干。父亲作为不大不小的军官,历来工作为主,家务基本是个甩手自在王,永平时常说,父亲一干家务就烦,有时会摔耙子,没有耐心,这一点遗传给了我,我就对一应俗务烦得不行,除非偶尔兴起主动要干,被迫的一概就是个没耐心烦。

手受伤后,一只手一直不敢太用劲,型煤厂装废铁的活也干不成了,回克山休养了一段,日子总得继续,大概在2003年左右,大哥去银川投奔二哥,二哥给租好了房子,准备了出摊卖烤肠烤玉米的车子。可是性格所限,做小买卖就是不行,便上山给人种树,后来二哥因故举家迁到山东东营卖包子,大哥便一个人留在银川谋生,那两年也是我们和大哥失联的时期,老二贴了寻人启事,我们差点就要报警寻人了。就在急切间,大哥电话打到了哈尔滨,原来他是山上没信号,用不了手机。当时每月工资是五百元,我推断老大是用不起手机。《贺兰山上的梦》写到过那段日子。

大哥很喜欢银川,说是冬暖夏凉,塞上江南,羊肉好吃,他还和我说以后我俩一起回去看看。银川我也没去过,以后如果去,想必心情会非常复杂,两个哥哥都在那里谋生了好几年,永平的若干个自我之一就依然生活在那座城中,只是我再也找不到他了。大哥虽已离世,在我,他却是还活着,只是不再和我见面,不再和我联系,只是安静地在练他的气罢了,我也再不能打扰他了。

3

漂泊无依对人的伤害是非常大的,我也只是到了2007年,自己也背井离乡孤身南下,才真正明白什么叫无家的漂泊之苦,艰难苦恨繁霜鬓,个中滋味,没有相同经验的很难理解和体会。2008年春天,二哥一家三口从东营来南京与我团聚,我们俩又联系远在银川的永平,让他也来南京,兄弟团聚。大哥7月初来到南京,我和二哥接站,远远看到老大从通道走出来,面色灰黄,瘦得几乎脱了相,小时候很可爱的小虎牙也变得过长了,二哥也很吃惊,怎么几年未见,不但老了,模样都变了。小时候我最听大哥的话,跟着他打拳,有些事只有他能劝动我,年纪老大,发现大哥也只是一个凡人,人群中矮小的身影毫不起眼,心中暗暗有些失落。

南方的热真是难熬,大哥刚来时,和我住,好几回下楼上班,居然转向走反了,向北走到学校外头去了,学生宿舍区是在南边,这下可是能找着北了哈哈。大哥说,人活着,越怕啥越来啥。他最怕熬夜,可他那学生宿舍值班员的三班倒的工作,早班还好,中班回家是半夜,也还好,最怕晚班,晚上十点半一直要熬到第二天早上七八点钟,中间还要把一个区几座楼逐层爬遍不止一次,电子打卡,真真受不了。苦那几个逼子儿可是太遭罪了。一开始850,最后几年才涨到一千几。

2009年马原来南京读大学,其实也是为了来陪我这个没有生存能力的破爹,大哥就搬出去自己租房过了。从物理上到精神上,有些人都是在无家的状态。大哥在他的诗《风中蚂蚁》里深刻地予以了表达——

风中的蚂蚁

它找不到离家的路和回家的路

它的巢穴已被尘土淹沒

它的两根触角被风扭断

像两根断了的树枝

它在地上小心翼翼地转着圈子

或在一片被风吹落的绿叶上来回奔跑

从叶子的这边奔跑到另一边

而折断了的触角,像两根天线

在奔跑中摆动着,搜索着

风从远处吹来,它还在一片叶子上

转来转去,焦急地兜着圈子

还在拚命寻找离家的路和回家的路

好像要赶在黄昏消失之前

大哥在两个地方住过,郑家营和蒋家街。租住的是城中村一百来块钱的民房,就是个偏厦子或曰小棚子,里边只能放下一张床,和电饭锅等一些杂物,那门就是个薄板,一脚就能踹开。我常问大哥害不害怕,可能是自小习武的缘故,大哥的警惕性很高,也不怕任何邪祟,正气很足。我让他睡觉时用椅子把门挤上,他说用不着。他每次下中班时都是半夜,得走几十分钟的夜路才能到家,我让他随身携带马原金工实习时做的一把铁锤防身,他也不要。他说,只要有人靠近他十米之内,对方的气场有没有恶意,他身体自动就有反应。金钱还是能解决不少具体问题的,每到这个时候,我就很自责,自己这一生完全投进了诗歌,没能创造出财富在物质上帮助到亲朋。有几回我没打招呼就去他住处,大哥很开心,我们俩就在他那小瘪屋里做泰国香米,炖豆腐,但有一次大姐要把他屋子彻底清理一下,大哥居然生气了,就是不让收拾,人的心理有时是别人无法体会的。

有可能是练功的人对环境更为敏感吧,大哥挑床挑得厉害,他在我家和二哥家都会睡不着,所以,过年三十晚上,我们三兄弟聚餐后,他往往也是半夜也得回自己的“家”,也就是那小瘪屋,一旦失眠,他无法练功,而工作又是那么难熬,累倒不太累,就是熬人。每到暑假,我回哈尔滨探亲,就把家交给大哥,我还会开玩笑地微信发状态称,马家现由一名拳法高手值守,有免费想死的就来吧。我家也同样是个陋室,除了书,可谓家徒四壁,但好歹能洗澡,有空调。大哥就说,他这是改天换地了。可就在我家,他也得适应好几天才能睡着,据说有一年大哥愣是觉得床上睡不踏实(难道怕睡着时张跟头打把势掉地上来?),居然放着两张大床不睡,跑方厅打地铺住了四十多天。说到底,人还是得有“一间自己的屋子”,哪怕看不见风景的房间,金窝银窝,不如自己的狗窝。

大哥与我共同的兴趣挺多,都喜欢瞎溜达,底层且是留平头的百姓,也只有瞎溜达看看热闹的份了,繁华富厚和我们只有半毛钱关系。我如果不是自强不息,于四十岁上跨专业考取文艺学博士,也会堕落成和大哥一样被买断工龄自谋生计或自寻死路的地步。我们兄弟俩常各处转转,大哥喜欢拍照,喜欢山水,我带他去过南京几乎所有好玩的地方,去过苏州,诗人小海招待过我们,去过杭州,诗人任轩和涂国文都招待过我们,去过上海城隍庙和长兴岛,去过西安,去过淮安,诗人梅尔对待我们如同家人。扬州和太原没来得及去,大哥非常喜欢山西的诗人赵泽汀、唐晋、非默、薛振海、赵树义、韩玉光等,他很盼望我能带他去和这些诗友玩玩,真是遗憾,因为我也没有太多机会和时间出门。

人需要自尊,别人尊不尊敬自己倒无所谓,人活着又不是为了让人尊重的。大哥自尊心特别强,从不求人,有困难都是自己忍,我好不容易找到个理由给了他一万块钱,他买了大屏的华为手机,喜欢得不得了,又看了牙,剩下的却又趁马原结婚塞回给我了,说什么也不收。有时想想真是悲哀,至亲之人的帮助也不接受,这固然是因为大哥心疼我,我那点工资也是苦钱,但有时也让你感觉这固执的拒绝也挺气人。我们老马家人这性格遗传。给予是慷慨,接受是优雅,我相信梅•萨藤的话是有点道理的。

大哥二哥家孩子的名字都是我给取的,燕玲燕超。家族遗传,大姐174,二哥182,我186或188,只有大哥170多,他总说是小时候挨饿营养不良造成的。侄子和我儿马原都是将近190的大汉,和我们站一起,大哥一下子成了小孩了。他在《当我还是个小男孩的时候》一诗中表达了这种身材不高的遗憾:

当我还是个小男孩的时候

经常躲在那条小河旁的柳条冲中

期望自己会长得高大并且强壮如牛

不过我认为牛有点儿笨,但很壮实

当我长大的时候,却让我大失所望

我既不高大也不强壮,甚至有点儿瘦小

很长一段时间,我总是对自己的个子

苦闷不已。可是没办法只好接受了

当我还是个小男孩的时候

我从来不和比我小的男孩玩

我认为,他们太幼稚太可笑了

他们和小女孩玩过家家跳格子丟口袋

或跳皮筋,那太没意思了,也不好玩

我只和比我大的男孩们玩

最小的也是和同龄的男孩

我们打冲锋仗或上大河游泳抓鱼

在柳条冲里藏猫猫或爬到树上掏鸟窝

下夹子捕麻雀弹玻璃球或拿弹弓打各种鸟儿

有时也偷偷地打别人家的窗玻璃

特别是在小满鸟来全的时节

有一种鸟儿长的很小,全身呈淡绿色

但是我们叫不出它的名字

后来我们给它起了个响亮的名字

叫瞎牛逼。虽然不太好听,但非常贴切

它在开满白色和红色花朵的山丁子树上

从这个枝头跳到另一个枝头

当我还是个小男孩的时候

我们有很多很多好玩的

大哥只有一个女儿,所以对我和二哥家的两个男孩十分疼爱,这两个侄儿又相继有了自己的儿子,大哥更是十分开心,这也是他人生的一大安慰,这种传统观念称不上保守封建,它是一种很正常的血缘情感。延续血脉是人类的一个大希望,哪怕是世界末日。2007年年末,我和大哥去了上海几次,大哥有心退休后在长兴岛修炼,他说北方冬天太冷,不适合练功。有一次我们在上海虹桥居然和马原碰到了一起,马原是出差路过,我们三个开心地在偌大的交通枢纽里度过了短暂的两小时。永平自己没有儿子,把马原视为己出,那天写下了一首感人的诗《在上海虹桥火车站的大厅里》:

我寻找我那高大壮硕的孩子

他转眼间就淹没在无数陌生的面孔中

我与我的侄子马原

偶遇在上海虹桥火车站的大厅里

他要去杭州,那里有他想要的生活

我们各有目的地,我们匆匆相见又分别

我陷入短暂的喜悦和更大的失落里

我望着他的眼睛,我问他

什么时候能让我看见侄孙子

他说:这不好确定!

然后我接着说:要努力啊!

现在我已经六十岁了

转瞬间已到了我父亲去世的年纪

2017.10.26于上海虹桥火车站

4

大哥生活简单至极,这既是主动的选择,也是被逼无奈。他只能从嘴里省。除了抽点劣质烟,也许只有修炼能带给他快乐或是平静。去年春天我给大哥一条和天下,没两天就抽完了,我还有点诧异,实际上这就对了,有,就赶紧享受吧。我偶有饭局总是会喊上大哥,早期基本都会跟我去,后来觉得诗人也都俗不可耐,就不大出来了。大哥曾言,也就跟着我能吃点好吃的。他牙还不好,咬不动啥,我总会先点几个软和的菜。有一次我俩去食堂,我吃惊地发现,大哥只吃一个菜。

贫穷真是个魔鬼,它总是在嘲弄侮辱着我们。好在大哥退休后回到克山与女儿团聚的一年半好日子里,女儿小玲给他做了不少好吃的,大哥说都给他吃撑着了吃胖了。这是让我感到安慰的。为什么说是一年半好日子呢?大哥2017年末归乡,马上因水土不服病了一个半月,然后就是照顾罹患癌症的大姐秀琴,很长时间就睡大姐家沙发上,方便照顾她,一直坚持到大姐于2018年6月27日病逝,大哥甚至长达二十五天几乎不眠不休,试问谁能受得了,血压蹭蹭地高啊。我曾有连续一周失眠的经历,尽管什么工作都没有,也几乎让我崩溃。我比不了大哥,他太能吃苦了。2018年暑假和寒假我都没见着大哥,他短信里告诉我他要恢复下身体。我相信,他最后突发脑溢血,恐怕还是和血压有关。这样算起来,大哥真正安宁的好日子,也就是照顾完大姐、夏天开始和女儿共同生活的这段日子,也就一年半的时间,好短。

2019年春天,大哥可能是身体调理好了,静极思动。他在微信中写到,“自从南京回来,再也不能去陪伴我弟永波了,对此我心生疚!这生活有太多的无奈,有太多的不可抉择。也许这生活本来就是这样的,也许这生活本来就不应该是这样的。“

月19日,大哥重回南京看我。期间还随我和远帆去了趟西安,出席了母校校友文学联合会的年会,和我的老友,也是大哥的好友仝晓锋、王建民欢聚,大哥特别喜欢建民的儿子,他和建民还约定今年夏天去青海走走呢。大哥在宁的那段日子,我忙着教学,他忙着瞎溜达,6月4日于紫金山中,永平写下了他此生最后的一首诗《山中的路》。

《山中的路》

我喜欢山

当然不是这座山

而是另一座山

但我不想告诉你它的名字

我喜欢山里的每一条路

每一片绿叶里的风雨声和闪烁的阳光

那山里的每一条路都有许多人走过

但是也有没人走过的路

我喜欢山

更喜欢山中夜晚的月色

但今夜没有月亮

夜空一片漆黑

山上的人该山下的山下了

他们转眼间便消失在山中的路上

而留下来的仍然在那里

这时我不得不下山

沿着寂静的山路和灯光

2019.6.4于紫金山中。这是永平最后的诗

6月21日,兄弟俩飞回哈尔滨,那是大哥此生唯一一次坐飞机。他在哈尔滨盘桓数日,返回克山与女儿团聚。他们父女经过长达二十几年的分离,在大哥生命最后的两年中,父女俩把所有的话都唠开了,彼此的理解和情感也达到了此生的顶点,这也是我深感欣慰的。人需要及时沟通,需要相处,哪怕是血亲。

有些人天生就对生命意义怀有深刻的追求与渴望探知奥秘的热情,我所置身的家庭就是如此,大哥练气,小玲学佛,我则披戴主耶稣,取向不同,内里的动力都是对精神纯度和灵魂救赎的诉求。而大多数人对此是没有追求的,绝不会把它当作生活首要的目标。

大哥没能长寿,遗憾与否,分怎么看吧。62岁,总归比家严多了两年。本指望大哥能替我们活到至少75,再大,不敢想,可是……生命不在于时间长度,把自己要做的做完,就可以了。苟活百岁,也终成粪土,如大哥这样拳拳到肉真实干净地活过,功也练了,诗也写了,可以了,没啥好遗憾的。就是这样。

在痛苦中回忆往昔的幸福,在幸福中回忆往昔的痛苦,两者的感受是多么不同啊。

2020年1月10日,一个怎样的日子啊,我不想再说了。北方县城那寒冷凄凉黑暗烟雾茫茫的晨昏,此生和我亲爱的大哥的最后一面时,我对他说的那句话,“大哥,你怎么出了这么大的事啊!”不会有回应了。死亡,真是太真实了。

现在,这一切都过去了。不会再有大哥的诗《姐姐、绳子和土豆》里那种火烧火燎的饥饿,不会再有病痛,不会再有让本应享有尊严的人遭受无尽羞辱的贫穷,不会再有眼泪和悲伤。

一切,结束得那么真实。

20200203凌晨2点40~晚8点于冰城,0204上午修订

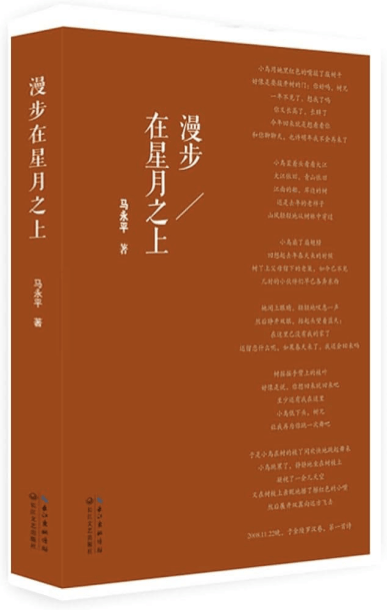

RED ONE, YONGPING’S 马永平 POETRY COLLECTION COVER

Three Poems of Ma Yongping 马永平 translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波 first published by Nasir Aijaz on Sindh Courier. Full BIO for Nasir Aijaz here in Volume 10

https://internationaltimes.it/ma-yongbo-poetry-road-trip-summer-tour-2025-volume-10/

Sindh Courier https://sindhcourier.com/poetry-the-path-up-the-mountain/

The Path Up the Mountain and the Path Down

Late at night, I take a walk on Purple Mountain,

along a stone-paved path leading upward,

wandering aimlessly.

The rising moon hangs between the branches of an oak tree,

around me, trees emerge in the dim light as

dark shadows, like figures,

standing silently there.

The night sky is vast, stars twinkle,

the mountain is silent. I walk slowly,

as if in a dream. I lose my way,

unsure how far the path to the summit remains,

nor how close the path down might be.

Suddenly, at a bend in the path,

two dark shadows flash toward me,

seeming to float before me in an instant.

I stop, gaze, and wait.

One of the shadows asks, “Master,

excuse me, which way is the path down the mountain?”

I say, “I don’t know. I’m just wandering too,

lost like you.”

Who knows how to take this path

up the mountain and the path down?

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

上山的路和下山的路

深夜,我在紫金山散步

沿着一条石彻的小路向山上

漫无目的地走着

初升的月亮挂在橡树的枝桠间

四周的树朦胧中显现出

一个个黑影,像一个个人

静靜地站在那里

夜空辽阔,群星闪烁

山中寂静,我慢慢地走着

仿佛走在梦境里,我迷路了

不知道通往山顶的路还有多远

也不知道离下山的路有多近

突然,在小路的拐弯处

闪出两个黑影迎面而来

好像一瞬间就飘到了我的面前

我停住脚步,注视,等待

其中一个黑影问,这位师付

请问您,下山的路该怎么走

我说,不知道,我也是瞎走

和你们一样迷路了

这上山的路和下山的路

该怎么走,有谁知道

I Crouch and Dart Out from the Courtyard Gate

I’m watching, keeping an eye on my mother,

to see what she’s doing, to check if she’s noticing me.

I spot Yongbo playing with mud balls alone on the earthen pit,

but I don’t know who gave them to him—maybe his second brother,

Yonggang. My sister went out long ago to play hopscotch.

My mother is by the windowsill, sewing clothes on a treadle machine,

she hasn’t noticed me yet; I think this is the perfect chance.

I push the door open gently, fearing she might hear the creak—

if she does, I’ll never get out, stuck playing in the courtyard,

forced to stay within her line of sight. But what fun is there in that yard?

The great river is so much better, with mountains beside it,

the water murmurs, and you can clearly see fish swimming among the pebbles.

I crouch low, dart out from the courtyard gate, and vanish without a trace,

when I return from the river, wisps of kitchen smoke rise straight into the sky.

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

我猫着腰从院门一闪而出

我在观察,观察我的母亲

看她在干什么,看她是否在注意我

我看见永波自己在土坑上玩泥球

但我不知道是谁给他的,可能是他二哥

永刚吧,我的姐姐早就出去跳方格了

母亲在窗台旁用缝纫机做衣服

她没有注意到我,我想这可是个好机会

我轻轻的推开房门,我怕被母亲听见开门声

那我就别想出去了,只能在院子里玩耍

只能在她的视线里玩耍,可是那院子里

有什么好玩的。那条大河多好啊,旁边还有山

河水潺潺能清晰地看见鱼在鹅卵石间游来游去

我猫着腰从院门一闪而出,便无影无踪

当我从大河回来,一缕缕炊烟笔直地升起

Sister, Rope, and Potatoes

A ray of sunlight falls on the kang.

A hemp rope: one end tied to the window frame,

the other looped around his waist.

His world on the kang spans only a meter,

there are several cooked potatoes on it,

an old leather trunk to the west, a stack of quilts.

He crawls back and forth,

the hemp rope swinging ceaselessly,

sometimes potatoes block his path

he pushes them aside with a small hand,

sometimes he props himself against the windowsill to stand,

but not for long.

He stares at sparrows leaping on poplar branches outside,

at a distant field of corn.

On the ground stands a little girl,

toes raised, hands gripping the kang’s edge,

only her eyes showing over the edge as she watches him.

When he cries, she fishes potatoes from the pot

and tosses them onto the kang,

at first he takes a few bites,

but later just looks at them or plays with them.

As dusk falls, the girl stands outside the door,

he leans on the windowsill again, gazing out,

this day, only a rope, his sister,

and a few potatoes keep him company.

His mother, returning from the fields,

will bring the warmth of night.

Ma Yongping 马永平 Translated By Ma Yongbo 马永波

姐姐、绳子和土豆

一缕阳光照在炕上

一根麻绳,一头拴在窗框上

一头拴在他的腰间

他的世界在炕上只有一米范围

炕上有几个熟土豆

西面一个老式皮箱,一摞被褥

他在炕上爬来爬去

麻绳在不停摆动

有时土豆会挡住他的路

他用一只小手把它们扒拉到一边

有时他扶着窗台站起来

站不了多久

望着外面杨树上跳跃的麻雀

望着远处的一片玉米地

地上站着一个小女孩

翘着双脚,双手扒着炕沿

露出一双眼睛,看着他

他又时也会哭,她就从锅里

捞几个土豆扔在炕上

开始他还咬几口

后来只是看着或拿着玩

天色渐暗,小女孩站在门外

他又扶着窗台望着外面

这一天只有一根绳子和姐姐

还有几个土豆陪伴着他

下地干农活的母亲就要回来了

温暖的夜晚就要来临

Biography of the Author: Ma Yongping (1958–2020), a Chinese poet, native of Suihua, Heilongjiang Province, started writing poetry in 2008. He left behind more than 2,000 poems totalling over 20,000 lines. His posthumous collection Wandering Above the Stars and Moon, compiled by his younger brother Ma Yongbo, was published by Changjiang Literature and Art Publishing House in 2020.

Relevant Comments:

“Brother Yongping became a poet in middle age as if aided by divine inspiration, which is amazing! His works are rooted in his daily experiences, plain and simple, yet their purport rises above the mundane, reaching lofty spiritual heights.”

— Tong Xiaofeng (Poet, Director, Professor)

It’s rare to see poetry so simple nowadays—free of ambition or pretence. Life’s hardships often twist the heart into complexity, and desire and vanity can deform a person entirely—common in many eras, especially ours. But in Ma Yongping’s case, in his poetry, you find only plain, pure vision: he gazes long at equally simple things, bowing his head to them without ever trying to take from them or impose himself upon them. Perhaps that’s why, in this era of widespread spiritual decline, he became a drifter who endured hardship silently. If there’s a unique luster in him and his words, it’s only because he stays close to simple things, sharing their very essence.

— Zhao Song (Poet, Novelist, Art Critic)

Brother Yongping’s works carry a tranquil yet far-reaching intent, with images natural and intimate—even echoing neo-surrealism. I particularly admire the tenacity beneath their simplicity and even awkwardness. Almost every poem begins with the simplest words, hiding wit in clarity, sighing with resignation from a seemingly bright world. The final lines often descend abruptly, breaking rules while creating their own—he’s a master!

— Yan Rong (Poet, Doctor of Literature)

Brother Yongping’s poetry is genuine—devoid of pretence and needing no so-called “techniques.” Genuine poetry is what jolts our very soul the moment we encounter it. It speaks not only of his personal experience but, more importantly, reveals life’s truth in the simplest, plainest, most precise way—seeming effortless yet profoundly weighty.

— Yuan Ren (Poet, Novelist)

My elder brother Yongping’s poetry is plain and accessible, yet hides profound mysteries. His precise re-creation of childhood, expression of life’s brevity and familial love’s eternity, his high awareness as a Taoist practitioner merging with the universe, his mockery of metaphors that congeal things into abstractions, his call to uphold original beauty—all subtly blend the shared joys and sorrows of life, envisioning an ideal of harmony in a suffering world… Ma Yongping’s poetry is far from simple on the surface! Those with high enlightenment will smile knowingly at his verses; those with moderate understanding will debate their depths; but those with low insight may dismiss them.

— Ma Yongbo (Poet, Doctor of Literary Theory)

Image: Ma Yongbo 马永波 and Ma Yongping 马永平 his poet brother, Harbin, China

Specific photographic images/graphic art under individual copyright © to either Ma Yongbo 马永波 or Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

.