The Era of Flowing Long Hair – A Retrospective of Ma Yongbo’s Poetic Creation in University, date 1982 – 1986

a night river running in the dark night of hair

夜河奔流于头发的暗夜

spun black, woven with gossamer; smoother than a glass shining

midnight window. Each hair is a strand of dark night air;

dark night found along the edge of a white door.

Black so thin it is hardly black at all when single, but fixed as a swathe

they gather black into a startling silver edge of a dark wave,

dark defying night within dark night; each strand

within a silver hem

2nd April 2025

Response Poetry By Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

夜河奔流于头发的暗夜

a night river running in the dark night of hair

黑色纺成,轻纱编织;比午夜闪耀的窗玻璃

更光滑。每根头发都是一缕暗夜的空气;

沿着白门的边缘发现的暗夜。

黑色如此纤细,单根去看几乎不是黑色,但固定成一条带状

它们将黑色汇聚成一道黑色波浪,带有惊人的银边,

暗夜中富有挑战性的黑夜;每一缕

都带有一条银色的褶边

2025年4月2日

To sort out my poetic creation journey over the four years of university, I dug out fifteen long-dusted poetry exercise books. Quite solemnly, most of them had titles or inscriptions. For instance, on the title page of the earliest one, there was a line written in black pen: “To betray, I tear off all days to write poems,” covering the blue-inked phrase “Questions with No Need for Answers.” Looking back now, I truly lived up to my oath – I have been stubbornly writing poetry until today, without the slightest slack. I am not saying that I place the value of my life solely on poetry; rather, poetry embodies my pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty throughout my life. Over a fairly long period of time, it has helped me get through hardships and adversities.

The existing poems from 1983 start on November 21st, which should be the earliest origin traceable in my “personal poetic history.” On the whole, the works from 1983 and 1984 are highly lyrical and vivid in imagery, forming the basic foundation of my creativity. In term of themes, they cover nostalgia for hometown and childhood, friendship and love, plateau scenery, campus life, and so on. There are also some pure products of my imagination, such as yearnings for the scenery of the Jiangnan region (which I had never visited) and marine life (with which I had never had any contact). Images like “sunken ships,” “sea stars,” “fog bells,” “holds,” and “red sails · brown sails” were all expanded into long poems. For example, the image of “cafés” frequently appeared in my poems. In reality, though, I had never been to such a place back then, and I still rarely go now. This image was merely a response to fashion, as cafés always symbolise the encounter and separation of emotions. Poems of the 1980s contained some fixed images – guitars, raincoats, moons, doves, clover, and a girl reading sonnets – which basically pointed to the romantic distant place of “life elsewhere.” It was the influence of Yesenin, the “Nine Leaves School” poets, and the Misty Poets that shifted my writing from the bright, high-pitched style (which seemed unrelated to personal experience) to the exploration of personalised life experiences. They changed my perception; the world in my eyes was no longer so simple and bright, but became fragmented, complex, and rich like the view through a compound eye. I began to look at myself and the world from a different perspective.

My encounter with the “Nine Leaves School” poets, to some extent, shaped me. They were more exploratory, and Mu Dan, Zheng Min, and Chen Jingrong were among my favourites. This affection has lasted to this day. In the 1990s, I even visited Zheng Min twice. When I pursued a doctorate in Literary Theory in the new century, I took the “Nine Leaves School” as the research topic for my doctoral dissertation, sorting out its influential relationship with Western modernism. My love for the “Nine Leaves School” is also inseparable from an important factor: several of them were outstanding translators. In particular, Mu Dan’s translated poems provided us with rare nourishment during my university years, and Zheng Min, Yuan Kejia, Chen Jingrong, etc., were also accomplished translators.

Speaking of poetry translation, my first attempt was in a college English class. I was very curious about what foreigners were writing, so I translated a few poems by Black poets (I can’t remember the authors now). My beautiful female teacher discovered this and praised me, planting the seed of my love for translating poetry. Another factor was meeting Zhang Yunhai, a young teacher from the Northwest University of Political Science and Law at that time. He was only one year older than me and had just graduated from Shandong University and been assigned to Xi’an. Tong Xiaofeng and I often went to his staff dormitory to hang out. Once, I saw an English poetry collection spread out on his desk – a pamphlet by Robert Frost. At that time, English poetry collections were rarely seen, so I was very surprised and envious to see someone reading an entire original version. This also inspired my enthusiasm for foreign languages. In my October 1985 sequence “Legends: Portraits for Friends,” I wrote about Yunhai like this:

Standing up from the bamboo chair

you bumped shoulders with each of us

so many words left unsaid

the night faded along our long hair into morning

From Zhuangzi to Frost

it was always quiet

autumn was close to the window

and you sat by the window

Years later, Yunhai and I finally collaborated to translate and publish Kipling’s The Return of the Native, Hawthorne’s A Wonder-Book, and Gissing’s The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft. Yunhai’s translation style is concise and lively, and our cooperation can be said to have fulfilled a wish.

Since the New Culture Movement, every step of modern Chinese poetry has been inseparable from the catalysis and nourishment of translated poetry. Novel ideas, exotic imaginative spaces, unfamiliar rhetorical methods, and advanced poetic concepts have been enriching Chinese poetry and even the Chinese language itself. The influence of Western poetry on me is very complex and diverse. For example, Neruda’s expansiveness and ability to write about anything; the exploration of the subconscious by French Surrealist poets like Apollinaire, Eluard, and Reverdy; Lorca’s ballad style; the rebellion against instrumental rationality and reflection on the crisis of Western civilisation in Rimbaud’s Le Bateau ivre, Ginsberg’s Howl, and Eliot’s The Waste Land – all these have permeated my writing to varying degrees. Mayakovsky’s staircase poems were also widely popular among college students in the 1980s, as they echoed the high-spirited passion of adolescence and the yearning for distant places. As a representative figure of Futurism, Mayakovsky was tall, handsome, melancholy, and indignant in our minds – with a carrot in his suit pocket, he would take the stage to recite Cloud in Trousers, Spine Flute, and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin loudly. His suicide by gunshot later, supposedly because “the boat of life hit the reef of love,” aroused sighs from countless people. Of course, the reasons were probably not just personal; most initiators of the entire modernist literary movement paid a heavy price.

When it comes to the influence of early foreign poetry on me, I must mention the “Poetry Garden Translation Series” published by Hunan People’s Publishing House, such as Seven French Poets translated by Cheng Baoyi, Liang Zongdai’s Translated Poems, Modern French Poetry Anthology by Luo Luo, Modern English Poetry Anthology by Zha Liangzheng, and Dai Wangshu’s Translated Poems. These were all published in the early 1980s, around 1983 and 1984 – coincidentally, that was exactly when I developed my modern perception, which was inseparable from their guidance. As the saying goes, fate is the encounter between people. I was fortunate to encounter these pioneering poems during my self-shaping period. They forced me out of the conservative rut of seeing only light and no darkness and turned me towards modern consciousness, especially awakening my awareness and thinking about the alienated situation of human beings. After graduating from university, around 1987, I read Contemporary American Poetry Anthology translated by Zheng Min, which greatly broadened my horizons. In the 1990s, driven by pure passion, I began to translate a large number of Anglo-American postmodern poems. After eight years of hard work, I finally published two large-volume translations with Beijing Normal University Press at the end of the 20th century: American Poetry After 1940 and American Poetry After 1970. It should be said that after Zhao Yiheng and Zheng Min, my translations of American poetry were second to none in terms of quantity and influence. At that time, Gu Yifan, who was studying abroad across the ocean, sent me the original version of American Poetry After 1940, as well as a Bible and Auden’s poetry collection. Zhao Qiong, a female poet in Xi’an, copied American Poetry After 1970 for me – that’s how these two translations came into being.

Van Gogh’s life passion like burning sunflowers, Goethe’s green-clad young Werther who died for love, and Beethoven’s cry of seizing fate by the throat – all these once inspired a young man’s heart and became the stance in his blood. However, the romantic feelings embodied in Wordsworth’s daffodils, Shelley’s west wind, and Byron’s libertines are ultimately only traits of a certain period of life. They cannot burn continuously; they are brilliant yet short-lived, like shooting stars. The passion of Romanticism is bound to be balanced by the gravity of Classicism. My poetic development followed the same path. For a period of time, I even thought Romanticism was all wet weakness, paleness, and narcissism, and was more attracted by the coldness and solidity of Modernism. Of course, at that time, I did not have a comprehensive historical perspective and could not appreciate the essence of Romanticism. It was not until the late 1990s that I re-examined the legacy of the Romantics, fell in love with Keats, Blake, and Wordsworth with great enthusiasm, and began to translate some of their works. The source of Modernism lies deep within Romanticism. At that time, Whitman and Dickinson also did not truly enter my consciousness. Although reading Whitman was exciting, I did not feel the necessity to learn from him – probably because I thought he was a bit old-fashioned. When young, one tends to like poetry that is exploratory and innovative in technique. Dickinson, on the other hand, gave me a sense of narrowness. It was not until the 1990s, with the growth of experience, that I suddenly realised: Whitman’s “mixed sand and water” style is exactly what Chinese poetry (which tends to be sentimental and delicate) needs; Dickinson is not narrow, but profound. In the end, I expressed my belated respect to both of them through translating a large number of their poems and essays.

Looking back now, since 1983, my poems have not been limited to so-called poetic rhetoric. Instead, I began to use compound language, incorporating colloquial elements and adopting more obvious narrative techniques – or rather, expressing emotions through narration, which distinguishes them from the traditional subjective lyrical way. The absorption of colloquial elements helps capture immediate experiences and reflect their authentic nature. However, from the very beginning, I instinctively avoided the superficial writing style of petty bourgeoisie and focused on in-depth exploration. This is where my works differ from the post-Misty Poetry trend that emerged in the mid-to-late 1980s. Keeping a distance from the trend at that time was not deliberate; it was merely a natural instinct, a result of starting writing early, rather than being guided by theoretical thinking.

From 1983 to 1986, I also tried “stream-of-life” writing one after another. Most of these works used long sentences for elaboration and description, which were rich in life’s flavour but somewhat superficial – this is evident from the titles, such as April in a Small Town, Men of the North, Chronicle of the Summer of 1985, In the World, and Café in the Rain, and they were often sequences. At that time, influenced by existentialist philosophy, I explored the connection between objects and people.

Another notable path is the so-called “cultural epic,” especially the pseudo-epic writing inspired by the search for roots in Oriental culture. Such works, often long poems, were constructed with broad time and space as the background and fully utilised imagination. They can also be regarded as attempts to retrieve national cultural confidence. Themes included the Jataka tales of the Buddha, the migration of ancient tribes, Qu Yuan’s “Mountain Ghost,” and associations based on ancient relics (such as Banpo). Here are some titles: Resurrected Dream, Caravan, Muddy River, Stone Fire, Glacier, Dance of Shiva, The Third Day, Ancestors, Dream Bear, Sunflower, and Worries. Relatively more valuable is Seven Chapters of the Sun, written in November 1985. With Chāndogya Upaniṣad from The Fifty Upanishads as its deep structure, the poem is divided into seven parts: “Rising Sound,” “Guiding Chant,” “Beginning Chant,” “High Chant,” “Answering Chant,” “Fading Chant,” and “Concluding Chant.” The seven stages of the sun’s movement correspond to various changes in life, just as the saying goes: “The sun is eternal and unchanging; know that all things in the world depend on it.” For a while, I was obsessed with reading Indian philosophy – works like The Life Divine and Upanishads – though I just devoured them without full comprehension, and I’m not sure how much I actually understood. I remember that after finishing this long poem in the lecture hall, I kept trembling on my way back to the dormitory.

Regarding the influence of Misty Poetry on us, I particularly liked Bei Dao – his coldness and profound thinking inspired me. However, compared with the influence of the “Nine Leaves School” and foreign poetry, the Misty Poets did not have the effect of historical forerunners in the influence chain because there was no temporal distance. They were more like “elder brothers next door.” In my 1981 college entrance examination essay, I quoted Shu Ting’s poems at length, and I specifically mentioned this when I met her in the 1990s.

In retrospect, 1985 was a crucial turning point – I completely entered the inner world of modern poetry. For example, the previous expression of clear, typified emotions was replaced by the capture of more modern, indescribable feelings. Many poems were titled Untitled, as they attempted to express emotions that could only be grasped in a general direction – more personal, more hidden, even weird, such as the sequences Urban Sensations and Love Poems. Sometimes I also drew materials from movies and paintings to form intertextuality, such as poems about Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin. Xiaofeng, on the other hand, wrote a series of poems about musicians like Beethoven. As a form of intertextual writing, it emphasizes dialogue between oneself and forerunners in literary and artistic history, and also serves as self-motivation – for example, I once wrote poems about Kafka, Neruda, and Whitman. In this year, Xiaofeng and I co-printed several self-published poetry booklets, such as Silence. Xiaofeng designed the cover and drew illustrations inside; we each copied some poems by hand, then duplicated them into booklets, with the words “Experimental Work No. 1” marked on the cover. My handwriting was quite restrained, while Xiaofeng’s was very free and easy – which matched our different personalities. Usually, he talked endlessly, while I kept silent, “as gloomy as a revolver” – only when reciting on stage could I relax.

In 1985, Tong Xiaofeng graduated and stayed at the university as a teacher, so his dormitory became my most frequent haunt. Sometimes, when I looked out from my dormitory window and saw a figure moving in his window, I would run over to chat with him. Of course, we talked most about poetry. Until I graduated and left Xi’an in 1986, both the quantity and quality of my poems reached their peak during this period – clearly driven by the encouragement from friendship. Xiaofeng was very good at inspiring others. Unlike some poets who are fragile, sensitive, or even eccentric, he always appeared as a sunny and bright figure, a rare positive force. Modernism advocates using complex poetry to express the complex human society and individual experiences. In this sense, most of Xiaofeng’s poems have a transparent context and are not complex in surface form. However, I believe this simplicity comes from a higher realm achieved after overcoming complexity – just like a drop of water reflecting the brilliance of the entire sea. His poems are “complex simplicity,” not “simple complexity.” This requires wisdom and the sublimation from experience to abstraction. What’s more precious is that in this process of sublimation, the poet fully retains the richness of experience and thought itself, instead of making poetry a tool for “preaching.”

In 1986, my poetic creation during university reached a small peak, producing a number of works that I still cherish today, such as Kafka, In Autumn, I Will Be Tired, Existentialism, Red Tiles, and White Poplar. As Professor Shen Qi commented, these poems are as fresh as white poplars. When I was about to graduate from university, I published my so-called “debut work” – the long poem The Soil I Live and Die With – in the magazine Grassland based in Hohhot. Of course, this poem is not representative. I received a remuneration of more than 70 yuan for the first time in my life, which was a “huge sum” at that time. Xiaofeng accompanied me to buy a black silk “prince’s shirt,” and we also had some cold drinks. That night, we walked back to the school from Shaanxi Normal University all the way, chatting happily, and finally climbed over the wall covered with snails to get into the campus. In 1986, Xiaofeng’s poetry also reached a climax, writing a series of excellent works such as Amber, Thinking of Winter, Remembrance, and The Cup. That spring passed in the confusion of being about to enter society. Zhang Chenhong, a girl from the major of Biomedical Electronic Engineering, and I hosted a “Spark” poetry recital. The auditorium was packed with people, even the aisles were crowded. Since then, that era when people generally loved and respected poetry has gone forever. Because Zhang Chenhong was much shorter than me, she stood far away from me on the stage – the scene was very strange and a bit funny.

After graduation, in 1987, my poetic style changed drastically, opening up a new path of “narrative poetics.” A series of works represented by Going Alone to Watch a Soviet Movie on a Cold Winter Night pioneered the shift of Chinese poetry from pure lyricism to polyphonic narration, and eventually became a sort of “prominent discipline” in the 1990s, as seen in the widely influential Xiao Hui and other works.

Looking back on my creations during my university years, though they sometimes feel immature, on the whole, I can say “I have no regrets for my early works.” These fifteen thin poetry exercise books carry the original intention of my lifelong love and my arduous explorations. Even now, when I select my early poems from the perspective of someone who has been through it all, the number of works I am willing to keep is still quite considerable—counting up to more than 400. I would not be embarrassed to show these poems to others. Perhaps when the time is right, I can compile an Early Poetry Anthology. As of the end of 2022, I have written 2,400 poems over more than 40 years, among which dozens are long poems or large-scale poetic sequences, forming quite an impressive body of work. Moreover, these booklets from my university days often had solemn inscriptions or titles, such as Two Kinds of Azure, The Legend of Loquat Island, He is a Bandit, Always Trying to Sneak Attack the Sky, Dream Song No. 24, The Faceless Child, The Third Day of Starlight… Perhaps they encapsulate my emotional state and understanding of poetry at certain stages back then. The diverse experiments and vitality not only allowed us to smoothly integrate into the overall evolution of Chinese poetry in that era but also endowed us with unique insights. For instance, the subjectivity in our poems was different from that of the “collective spokesperson” in Misty Poetry; it was more personalised and independent. Although the “enlightenment narrative” of Misty Poetry attracted us temporarily, we eventually returned to individual subjectivity. The stance of antagonising the times transformed into a sentiment of oneness with all things, and we turned to the exploration of intersubjectivity—something that had not yet reached theoretical consciousness at the time but had already shown signs in textual practice. Thus, in the late 1980s and the mid-to-early 1990s, my writing showed a tendency to integrate lyricism, narration, reasoning, and dramatisation. Later, I successively initiated “meta-poetry” and objective writing, and then moved on to “difficult writing” in the new century. All these have become important markers in the evolution of Chinese poetic aesthetics.

Now that life has entered its early winter, looking back on the mental journey of my university years and that era where “poetry, love, and revolution” were a trinity, I am both moved by the ruthlessness of time’s passage and content with this passage because of continuous creativity. I should be grateful for the guidance of the Muse—I have not strayed from the path in this life, nor changed my original intention. The joys and sorrows of life have all been transformed into poems of varying lengths, which in itself is an extremely precious gift.

December 17-20, 2022, Luohan Lane, Nanjing

Image:A group photo of the winners of the Xi’an Jiaotong University Annual Sakura Literature Award. Ma Yongbo is the fourth from the left in the second row,the fourth from the left in the third row is Tong Xiaofeng

长发飘飘的年代——马永波大学时代诗歌创作的回顾

为了梳理大学四年的诗歌创作历程,我翻出了尘封已久的诗歌练习册,一共有十五本,它们往往还煞有介事地带有书名或题词,比如最早的这本,扉页上用黑笔写着“为了背叛,我撕下所有的日子写诗”,覆盖在蓝色钢笔的“不需答案的问题”上面。现在看来,我果真践行了自己的誓言,一直固执地写诗,直到今日,未有丝毫的松懈。我并不是说我将自己人生的价值单单寄托在诗歌上,而是说诗歌集中体现了我一生中对真善美的追求,它在相当漫长的时间跨度里,帮助我度过了艰难与困厄。

现存的1983年的诗作,是从11月21日开始的,这应该也是我的“个人诗歌史”可以追溯的最初原点。83年和84年的作品,总体看来,抒情性和画面感较强,这是我的创作的一个基本底色。从题材上看,怀念故乡与童年、友情和爱情、高原风物、校园生活等,不一而足,还有一些纯粹属于想象力的产物,如对从未亲历过的江南风光、从未有过接触的海洋生活的向往,“沉船”、“海星星”、“雾钟”、“底舱”、“红帆·褐帆”等等,都敷衍成长诗。再比如,“咖啡馆”的意象频频进入诗中,可实际上,当时我从未去过这种场所,甚至到现在,也基本不去,这种意象仅仅是对时尚的一种反应而已,咖啡馆总是意味着情感的相遇与别离。80年代的诗有一些固定的意象,如吉他、雨披、月亮、鸽子、三叶草和读十四行诗的少女,它们基本都指向“生活在别处”的浪漫远方。那时,真正把我从那种明朗高调、与个人体验似乎无甚关联的写作,转向对个人化生命经验的挖掘上来的,应该是叶赛宁和“九叶诗派”,加上朦胧诗的影响。它们改变了我的感性,我眼中的世界不再是那么单纯明亮,而是如复眼中一般分裂、复杂和丰富起来,我开始以另一种眼光来看待自己和世界。

我与“九叶诗派”的相遇,某种程度上成就了我,他们更具有探索性,穆旦、郑敏、陈敬容,是我较为喜爱的。这种情愫一直绵延至今,以至于90年代我曾两次登门拜访郑敏,并在新世纪攻读文艺学博士时,将“九叶诗派”作为博士论文的研究课题,梳理了它与西方现代主义之间的影响关系。而我之喜爱“九叶”,也离不开一个很重要的因素,他们中有好几位都是出色的翻译家,尤其穆旦的翻译诗,在大学时代就给我们提供了不可多得的营养,郑敏、袁可嘉、陈敬容等,也都是成就斐然的翻译家。

说起诗歌翻译,我的最初尝试是在大学英语的课堂上,我对外国人到底在写些什么感到十分好奇,就翻译了几首黑人的诗,也记不清作者是谁了,结果被漂亮的女老师发现,得到了她的夸奖,自此埋下了热爱翻译诗的种子。另一个因素是当时结识了西北政法大学的青年教师张云海,他只比我大了一岁,刚刚从山东大学毕业分配到西安,我和仝晓锋常去他的教工宿舍玩儿。有一回我看见桌子上摊开着一本英文诗集,是罗伯特·弗罗斯特的一个小册子,那时根本见不到什么英文诗集,冷不丁看见一个人在读整本的原文,非常吃惊和羡慕。这也激发了我对外语的热情。我在1985年10月的组诗《传说:给朋友们画像》中这样写到云海:

从竹椅中站起来

你和我们每个人都撞了下肩膀

许多话没有说

夜晚就沿我们的长发褪色成早晨

从庄子到弗罗斯特

始终很宁静

秋天离窗子很近

你就坐在窗前

多年以后,我和云海终于联手合作,翻译出版了吉卜林的《回到家乡的人们》、霍桑的《奇迹书》和乔治·吉辛的《四季随笔》,云海的译笔简洁明快,我们的合作也算是圆了一桩心愿。

从新文化运动以来,汉语新诗的每一步,都离不开翻译诗的催化和滋养,新颖的思想、异国情调的想象空间、陌生的修辞方式和领先的诗学理念,都在一直丰富着汉语诗歌乃至汉语本身。西方诗歌对我的影响是十分复杂和多样化的。比如聂鲁达的开阔和无物不可入诗,比如法国超现实主义诗人阿波里奈、艾吕雅、勒韦尔迪对潜意识的探索,比如洛尔迦的歌谣体,兰波的《醉舟》、金斯堡的《嚎叫》和艾略特的《荒原》中对工具理性的反叛和对西方文明危机的反思,都不同程度地渗透进了我的写作。马雅科夫斯基的阶梯诗也受到80年代大学生的普遍欢迎,它契合了青春期昂扬的激情和对远方的渴望。作为未来主义的代表人物,我们心中的马雅科夫斯基高大英俊忧郁激愤,西装口袋里插着一根胡萝卜,上台大声朗诵《穿裤子的云》、《脊柱横笛》和《弗拉基米尔·伊里奇·列宁》,他后来因为“生命的小船遇上了爱情的暗礁”而饮弹自尽,也引起无数人的嗟叹,当然,其中原因恐怕不只是个人所致,整个现代主义文学运动中,主要的发起者都付出了重大代价。

涉及到早年外国诗歌对我的影响,必须要提到湖南人民出版社的“诗苑译林”丛书,程抱一译的《法国七人诗选》、《梁宗岱译诗集》、罗洛的《法国现代诗选》、查良铮的《英国现代诗选》和《戴望舒译诗集》等,它们均出版于80年代前期,83年、84年左右,而我进入现代感性也正好是在同一时期,可以说是和它们的引领分不开的。正所谓命运就是人与人的相遇,我很幸运地在自我塑型时期便适时地遇见了这些走在前列的诗歌,它们将我从保守的只见光明不见黑暗的窠臼中强行扭转到现代意识上面来,尤其是开启了我对人类异化处境的觉知和思考。大学毕业之后,大概在1987年,我又读到了郑敏译的《美国当代诗选》,它大大打开了我的眼界,到了90年代,我自己则全凭一腔热血开始大量翻译英美的后现代诗歌,经过八年苦干,终于在20世纪末由北京师范大学出版社出版了两卷大部头的译著,《1940年后的美国诗歌》和《1970年后的美国诗歌》。应该说,在赵毅衡和郑敏之后,我翻译的美国诗歌在数量和影响面上都是首屈一指的。当时是远在大洋彼岸求学的顾宜凡给我寄来的《40后》的原版书,还有《圣经》和奥登的诗集,西安的女诗人赵琼则给我复印了《70后》,这才有了这两卷译著的问世。

梵高燃烧的向日葵一般的生命激情、歌德为情赴死的绿衣少年维特、贝多芬扼住命运咽喉的呐喊,都曾激励过一个青年人的心,成为他血液中的姿态。然而,华兹华斯的水仙、雪莱的西风和拜伦的登徒子,那种浪漫情怀终究只是生命某一个时期的特质,它们不可能持续地燃烧,它们辉煌而短暂,犹如流星,浪漫主义的激荡势必要被古典主义的凝重所平衡。我的诗歌流程也是如此。有一段时间,我甚至觉得浪漫主义都是湿漉漉的软弱、苍白和自恋,现代主义的冷峻和坚实更加吸引了我的兴趣,当然,那时我还不具备整全的历史视野,无法体会到浪漫主义的精髓,以至于到了90年代末期,我才重新审视浪漫派的遗产,以极大热情爱上了济慈、布莱克和华兹华斯,并着手翻译出了他们的若干篇什。现代主义的源头就在浪漫主义的深处。当时的惠特曼和迪金森也没有真正进入我的意识,惠特曼虽然读起来令人激动,但并不觉得有什么可资学习的必要性,其中原因恐怕还是感觉他有点老套,年轻时多喜欢探索性强的、技巧新颖的诗歌,而迪金森则给人一种紧缩的狭窄之感。及至到了90年代,随着经验的增长,我才恍然大悟,惠特曼的泥沙俱下恰恰是偏于情调和精致的汉语诗歌所需要的,迪金森也不是狭窄,而是深刻。最后,我以对两者诗文的大量翻译向他们表达了迟到的敬意。

现在看来,从83年起,我的诗就已经不局限于所谓的诗化修辞,而开始采用复合的语言,有了口语化的成分,也有了较为明显的叙述化的手段,或者说是以叙述来抒情,以区别于传统的主观抒情方式,口语化成分的吸纳有助于捕捉当下性的经验,体现其本真的质地,但从一开始,我就本能地避免了小市民气的平面化写作,而注重深度的开掘。这是与80年代中后期涌现的后朦胧诗潮有所区别的地方。当时与潮流拉开距离并不是刻意为之,仅仅是一种天性和本能,是先行进入写作所自然带来的结果,而非理论思考的引领。

从83年到86年,我也陆续尝试过“生活流”的写作,多是长句子铺陈和描摹,生活气息浓郁但有些流于表象,从标题上就可见一斑,如《小城四月》、《北方的男人》、《八五年夏天纪事》、《在人间》、《雨中咖啡馆》等,而且往往都是组诗。那时候受存在主义哲学的影响,对物与人之间的关联域有过探索。

另一个值得一提的路线是所谓的“文化史诗”,尤其对东方文化的寻根所催发的伪史诗写作。这种写作多以阔大的时空为背景、充分调动想象力的作用铺陈而成,篇幅较大,多为长诗,它们也不失为寻回民族文化自信的某种尝试。写佛陀的本生故事、古代部落的迁徙、屈原的山鬼、依据古代遗存展开的联想(如《半坡》)等等,姑且开列一些诗题,如《复活的梦》、《大篷车》、《泥之河》、《石头的火》、《冰河》、《湿婆之舞》、《第三日》、《祖先》、《梦熊》、《向日葵》、《心事》等。相对较有价值的是写于1985年11月的《太阳七章》,此诗以《五十奥义书》中的《唱赞奥义书》为深层结构,分为“兴声”、“导唱”、“始唱”、“高唱”、“答唱”、“阑唱”和“结唱”七部分,以太阳运行的七个阶段对应人生诸般变化,正所谓“太阳者,恒常同一,当知此万事万物,皆依于彼”。有段时间我读印度哲学读得入迷,什么《神圣人生论》啊,《奥义书》啊,都囫囵吞枣地啃了下来,可实际上到底读懂了多少,也未可知。记得我在阶梯教室写完这首长诗,回宿舍的路上一直在发抖。

就朦胧诗对我们的影响而言,我较为喜欢北岛,他的冷峻和深沉的思考,都给了我以启发。但是和“九叶诗派”及外国诗歌的影响相比,因为没有拉开时间的距离,朦胧诗派没有构成影响链条上的历史先行者的效应,他们更多的像是“邻家哥哥”。1981年高考作文我就曾大段引用舒婷的诗,90年代见到她时我还特意提起。

回头看去,1985年是一个关键性的转折,我彻底进入了现代诗的内部,例如,以往明朗的类型化情感的抒发让位给一种更具现代性的莫名情绪的捕捉,诸多诗都以《无题》来命名,它们试图表达的是只在大致向度上可以把握的情绪,更加个人化,更加隐秘,甚至诡异。如组诗《城市感觉》和《情诗》。有时也会从电影和绘画中取材,形成互文,如写梵高、塞尚、高更的诗,晓锋则有一系列写音乐家如贝多芬的诗。作为一种互文性的写作,它强调的是自我与文艺历史上的先行者之间的对话,也是对自我的激励,如我曾写过关于卡夫卡、聂鲁达、惠特曼的诗。这一年,我和晓锋合出了若干种自印诗册,如《寂静》,晓锋设计了封面、绘制了内文插图,我俩各自手抄了一些诗,然后复印成册,封面上标有“实验作品之一”的字样。我的字迹颇为拘谨,晓锋的字则十分潇洒,这与我们不同的性格是符合的。平时总是他滔滔不绝,我则一声不吭,“阴沉得像一把左轮手枪”,只有在上台朗诵时才能放得开。

1985年晓锋毕业留校,他的宿舍就成了我最常光顾的地方,有时我从自己宿舍的窗口望去,如果看见他的窗口有人影晃动,我就会跑过去找他聊天,当然,聊得最多的还是诗歌,一直到86年我毕业离开西安,这期间我的诗歌产量和质量都是最高的,这里显然有来自友情的鼓励所起的推动作用。晓锋非常善于激励别人,他没有一般诗人的那种脆弱敏感甚至怪异,而多以阳光明朗的形象出现,是一种难得的正向力量。现代主义主张用复杂的诗歌来表现复杂的人类社会和个体经验。从这个意义上说,晓锋的大多数诗语境透明,表面形态并不复杂,但我认为,这种单纯来自于克服了复杂性之后达到的一个更高的境界,正好像一滴水反映着整个大海的光辉,他的诗是复杂的单纯,而非单纯的复杂。这需要智慧,需要从经验到抽象的升华,更为可贵的是,在这种升华过程中,诗人充分保留了经验和思想本身的丰富性,而没有使诗成为“载道”的工具。

1986年,我大学时代的诗歌创作达到了一个小的巅峰,产生了一批至今还让我留恋的作品,如《卡夫卡》、《秋天,我会疲倦》、《存在主义》、《红瓦片》、《白杨》等,这些诗就像沈奇教授评价的那样,像白桦树一样清新。大学临毕业时,我在呼和浩特的《草原》杂志上发表了我的所谓“处女作”,长诗《我生死相依的泥土》,这首诗当然不具有什么代表性。我生平头一次得到稿费,有七十多元,在当时已是一笔“巨款”,晓锋陪我买了一件黑绸子的王子衫,我们又吃了冷饮,那晚我们两个一直从陕师大步行走回学校,一路快乐地聊天,最后从爬满蜗牛的围墙翻进学校。1986年,晓锋的诗歌也达到了一个高潮,写下了《琥珀》、《想起冬天》、《怀念》、《杯子》等一系列佳作。那一年的春天,就在即将步入社会的迷茫中过去了。我和生物医学电子工程专业的女生张晨红主持了一届“星火”朗诵会,礼堂里人满为患,连过道都挤满了人,那个人们普遍热爱和尊重诗歌的年代自此一去不复返了。因为身材比我矮了很多,张晨红在台上站得离我远远的,那场面十分古怪,又有点滑稽。

毕业后,到了1987年,我的诗风大变,开启了“叙述诗学”的新路,比如以《寒冷的冬夜独自去看一场苏联电影》为代表的一系列作品,在汉语诗歌由单纯的抒情转向复调的述说方面,开创了先河,而终至于在90年代成为某种“显学”,比如影响广泛的《小慧》等。

检视大学时代的创作,虽时有稚嫩之感,但总体上可以说是“不悔少作”。十五本薄薄的诗歌练习册,承载的是我一生热爱的初衷和艰辛的探索。即便此刻以过来人的眼光,对早年诗歌进行苛刻的遴选,我愿意留存的作品数量依然十分可观,统计下来有四百首之多,这些诗拿来示人我是不会脸红的。也许等时机成熟,可以编一本《早期诗选》,统计到现下的2022年底,四十来年中我已经写出了2400首诗,其中有数十首还是长诗或大型组诗,亦蔚然大观矣。而大学期间的这些小册子往往还有庄重其事的题词或书名,如《两种蔚蓝》《枇杷岛的传说》《他是一名匪徒,总想偷袭天空》《梦歌第二十四号》《没有面孔的孩子》《星光第三日》……也许它们概括了当时某些阶段的情绪状态和对诗的认知。多方面的实验和活力,不但能让我们顺利地汇入那个年代汉语诗歌的整体流变,而且有自己独到的创见。比如说,我们诗中的主体性,已经不同于朦胧诗的集体代言人的主体性,而更加个人化,更加独立,朦胧诗的“启蒙叙事”虽暂时吸引了我们,但最终我们还是还原到了个体主体性之上,与时代拮抗转变为万物一体的情怀,转向了当时尚未达到理论自觉但在文本实践上已然露出端倪的主体间性的探索上面。于是,在80年代末期和90年代中前期,我的写作呈现将抒情、叙述、论理和戏剧化综合起来的倾向,其后又相继首倡“元诗歌”与客观化写作,再到新世纪的难度写作,这些都构成了汉语诗美学流变的重要标志。

在人生已进入初冬的时节,回顾大学时代的心路历程,回顾那个“诗歌、爱情与革命”三位一体的年代,既让人感慨时间流逝之无情,又让人因为持续性的创造而安于这时间的流逝。应该感恩缪斯的引领,这一生没有迷途,不改初衷,人生悲喜,都化作了长长短短的诗篇,这本身就是至为宝贵的恩赐

2022年12月17-20日于南京罗汉巷

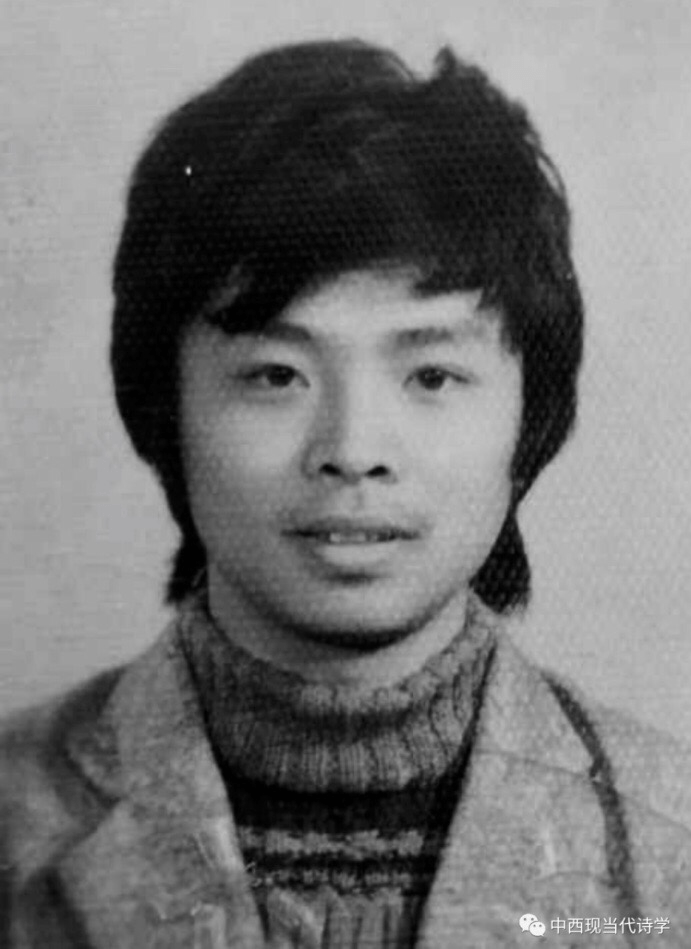

Image: Tong Xiaofeng 仝晓锋

Tong Xiaofeng 仝晓锋 on Yongbo, the Born Poet

I first met Yongbo at a gathering of the Spark Society. He was so tall that one had to look up to him up close. By nature, he was lonely, taciturn, and quiet, with a pair of melancholy eyes that made him seem as if he were always sleepwalking, detached from everyone else. Conversing with him felt like he was always half a beat slow—only when he recited his own works would he radiate the passion and brilliance of a poet. Yongbo’s early poems were clear and lyrical. When published in Spark Poetry News or poetry journals, he always signed them “Qingxue” (Sunny Snow), perhaps hinting at his origins from the cold northern borderlands.

Love Poem

Loving you across a table

across many epochs

Fresh dreams, receding tides

wooden flowers bloom under my fingers

the real sea stands afar, like planed wood

Loving you through layers of clothes

across the solitary sea

The roof is higher than our raised heads

the bright moon is higher than the roof

I love you from multiple angles

through layers of uncleared ashes

We both belong to this door

always on the verge of being pushed into harsh winters

In the house exists the one and only night

we are destined to part

destined to disappear at a moment’s notice

Loving you through skin

loving you through the night

gazing at you across gusts of wind

I am in the distance

through several female’s faces

loving you and then losing you

13 December 1985, translated by Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨 & Ma Yongbo 马永波

First published International Times, IT, 13th July 2024

Kafka

Evening falls, and the rain begins

Kafka’s grey wool coat

deepens in colour

his cane sinks into the mud

the darkness in his eye sockets

reveals many laughter lines from years past

he walks across the railway bridge

to greet a young girl

the thick fog quickly obscures everything

he’s aged, otherwise he wouldn’t smile at people like this

the rain falls, droplets rolling off his collar

creating islands in his heart

writing is futile now

he knows the fog will dissipate

and then he will sit down to rest

a few insects on a flower

glimmering, whispering softly

April 7, 1986

Pablo Neruda

In winter, you go to find him

on the snow-covered streets of Prague

you stand in front of a house

the door is locked, he is talking with time

because of the cold, you hide in a cinema

the wounded stones lose their language

you stand at the corner waiting for him to pass

you are looking for him by the sea

he should be everywhere you go

talking with those wounded stones

or a boy smiling alone

that voice is like your own face

you don’t need to look for him

you might meet him crossing the streets or coal mines

you can also ride on a wooden chair

say, I love you, please come out

he will then say something loudly and come to the yard

carrying the scent of fish and saltpeter

at that moment, you must prepare firewood

the winters in Prague are very cold

in front of the house where the heroes departed,

he had stood for a long time

July 19, 1986

originally published by Nasir Aijaz in the Sindh Courier

https://sindhcourier.com/kafka-poetry-from-china/

See Ma Yongbo Poetry Road Trip Volume 10 for Nasir Aijaz’s Bio

https://internationaltimes.it/ma-yongbo-poetry-road-trip-summer-tour-2025-volume-10/

Red Roof Tiles

At last, it rains again

the red roof tiles glisten and swim like scales

when we were little, we swam in water

blowing bubbles

Seeing you in the rain, always with loose hair

your voice veiled by a layer of mist

watching how you run upstairs

laughing as you stamp your feet at the door

raindrops, like lamps, light up my lower body

you are soaked, green as green can be

the plums in the low-lying field are always red

I wonder if you are still standing in the rain now

having lent your umbrella away

if winding streams still crawl over your feet

in the rain, there are always voices

calling a name too faint to hear

Then I spend the whole day without eating or speaking

lying on the wooden planks

waiting for the plum in your mouth to light up my body in the soil

When I was little, I was a bit mischievous

in the morning, I’d feign stomachache to skip running

behind the red brick stack, I touched her shirt, green through and through

at twelve, I walked through the wind

accepting these early autumn eyes

like the wet plums in the low-lying field

At last, it rains again

I still have to return

return as green as green can be

July 1986

Yongbo was talented beyond his years. He wrote poems extremely quickly, barely revising them—truly capable of “composing ten thousand words while leaning on a horse.” If we didn’t see each other for a few days, he would have written a thick notebook full of poems. His poems had extremely strong visual imagery, which aligned perfectly with my poetic taste, so we soon became inseparable buddies.

After Yongbo and I took over the Spark Society, we immediately upgraded the original publication—from hand-carved prints to typed copies, and greatly increased its thickness. It focused mainly on poetry, with only a small amount of essays and prose. We named the new Spark publication Sun City, but the school’s Communist Youth League committee official in charge of student clubs disagreed, arguing that it was inappropriate to share the same name as the masterpiece by utopian socialist writer Campanella. We had no choice but to rename it The Young City. Quance and I designed the cover. At that time, we admired the abstract artist Paul Klee greatly, so the cover was extremely minimalist, like a child’s naive drawing.

Yongbo’s and my poetry writing reached their peak around this time—we would each write a thick notebook full of poems every month. We often appeared, one tall and one short, at literary salons and poetry recitals at major universities in Shaanxi. Back then, wherever we went, I would speak passionately like an orator, while Yongbo stood silently aside—”as gloomy as a revolver,” in his own words.

In 1985, I graduated and stayed at the university to work in the academic journal editorial office. My single dormitory became a gathering spot for the Spark Society poets. By then, due to the school’s tight budget, The Young City had been forced to cease publication. So Yongbo and I had to print several poetry collections on our own, either individually or jointly: Silence, The Emperor, Shadow’s Adagio, etc.

In July 1986, Yongbo graduated. As a graduate majoring in software, he was unexpectedly assigned to the technical section of the Harbin Rolling Stock Factory, which made me faintly worried. When we parted at the train station, we earnestly urged each other to keep motivating one another, work together, and carve out a place for ourselves in China’s contemporary poetry scene.

Later, I deeply felt that my poetry writing had hit a bottleneck and I couldn’t break free from the limitations of my established style. So I turned to another field I loved—film. Yongbo, however, fought alone on the thorny path of poetry, going further and further. In 1991, Hong Kong’s Wenguang Publishing House included his first poetry collection Red Bird in its “New Era Poets Series.” A long elegy for his father, To My Departed Father, attracted widespread attention and marked Yongbo’s entry into a higher stage of poetic writing. As expected, in the 1990s, his poetic craftsmanship became increasingly polished, and his personal creation reached its zenith. In particular, the completion of dozens of long poems propelled him into the ranks of China’s most important contemporary poets.

In 1999, Taiwan’s Tangshan Publishing House included his second poetry collection Summer Played at Two Speeds in its “Mainland Avant-Garde Poetry Series.” Editor Huang Liang’s evaluation of him was extremely accurate: “Ma Yongbo’s poems are serene and generous. Their spiritual core is solid, and their magnetic field is broad, imbued with the crisp aura of the cold northern lands. He has opened up a vast and inestimable mysterious poetic realm for Chinese poetry.”

In 2015, his third poetry collection—and his first on the mainland—Travels in Words was published. I specially hosted a seminar and two recitals in Xi’an, the hometown of his poetic creativity, as a summary and review of his decades of writing poetry!

Last year, Yongbo and I began planning to shoot a poetry film based on his poems, titled after his collection Travels in Words. The film will be woven together with the poet’s verses, showcasing the evolution and growth of his spiritual world. Through the triple timelines of childhood, youth, and reality, it will profoundly reveal the marks left by great social changes on the poet’s fate, as well as his contemplation and meditation on the existence of life.

I am well aware of how difficult it is to make such an extremely unconventional art film in today’s highly commercialised and entertainment-oriented China. Yet I still firmly believe that heaven will grant me the chance to accomplish it.

I see this film as an eternal tribute to our youthful oath and poetic friendship!

May 5, 2019

Image: Yongbo in his third year of university, because of his tall stature, he could never buy clothes that fitted him.

仝晓锋:天生的诗人永波

初识永波是在星火社的一次聚会上,他因为个子太高,近处看他需要仰视,他生性落寞、寡言安静,一双忧郁的眼睛让人感觉他好像总梦游般疏离于大家。与他交流,也好像总慢半拍,只有当他朗诵自己作品的时候,才焕发出诗人的激情和光彩。永波早期的诗歌明净抒情,在星火诗报或诗刊上发表总署名晴雪。可能是暗示他来自寒冷的北国边疆。

情诗

隔着一张桌子爱你

隔着许多年代

新鲜的梦,呈现低潮的海水

纷纷的木花在手指下涌现

真实的海立在远处,像一块刨平的木板

隔着许多层衣服爱你

隔着惟一的海

屋顶比我们支起的头更高

明月比屋顶更高

我从各个角度爱你

隔着许多未清理的灰烬

我们同属于这扇门

随时都可能被推向严冬

屋子里是惟一一个夜晚

我们注定要离开

注定在一个时刻消失

隔着皮肤爱你

隔着夜晚爱你

隔着一阵阵风,盯视你

我在远方

隔着几张女人的脸

爱你,然后失去你

1985.12.13

卡夫卡

傍晚,开始下雨了

卡夫卡的灰呢大衣

颜色更深了

手杖陷在污泥里

眼眶中的黑暗

浮现许多年前的笑纹

他走过铁路桥

向一个女孩子问好

浓雾很快就遮去了一切

他老了,否则不会这样对人微笑

雨在下,水珠从衣领上滚落

在他心里溅起一片片岛屿

写作是没有用的了

他知道雾会散去

那时他将坐下来休息

几只昆虫在一朵花上

闪闪发光,细声曼语

1986.4.7

巴勃罗·聂鲁达

冬天,我去找他

在布拉格积雪的街道

他站在一座房子前面

房门锁着,他在和时间交谈

因为寒冷,我躲入影院

受伤的石头失去了语言

我站在拐角里等他过去

其实我是在海边找他

他应该在我走动的任何地方

和那些受伤的石头或者

一个独自微笑的男孩交谈

那声音像你自己的面容

其实你也不用去找他

你可以碰见他穿过街道和煤矿

你也可以骑上木椅

说我爱您就请您出来

他就会大声说着什么来到院子里

带着鱼和硝石的气息

这时你要备好劈柴

布拉格的冬天很冷

英雄离去的屋子前,他已站了很久

1986.7

红瓦片

终于又下雨了

红瓦片又在粼粼游动

很小的时候,我们在水中游过

吐过泡沫

雨中看你总披散开头发

声音隔着一层雾气

看你怎样跑上楼

哈哈笑着在门口跺脚

雨珠像灯照亮了我的下半身

你湿得很绿很绿了

低洼地的李子总是红的

我不知道你现在是否还淋着雨

把伞借人

弯弯曲曲的水流是否还从你的脚上爬过

雨中总有些声音

叫着一个名字

已听不清楚

这时我就整天不吃饭也不讲话

躺在木板上

等着你嘴里的李子照亮我泥土中的身体

很小的时候我有点邪

早上我肚子疼不去跑步

红砖垛后我触了触她绿透了的衫子

十二岁便从风中走过去了

接受了这个初秋的眼睛

像低洼地里湿湿的李子

终于又下雨了

我仍旧要回来

要很绿很绿地回来

1986.7

永波才大,写诗及其迅疾,几乎不改,有倚马万言之能,几天不见,就会写出厚厚的一本。他的诗歌视觉意象十分强烈,这和我诗歌趣味非常一致,所以很快成为形影不离的哥们。

启东、晓楠、强华、宜凡毕业后,我两接管了星火社,并立刻把原来的刊物升级,从手刻变为打字,厚度也增加很多,主要以诗歌为主,只有少量的随笔和散文,我俩把新的星火刊物定名为《太阳城》,但学校团委主管学生社团的领导不同意,认为和空想社会主义作家康帕内拉的代表作同名,不好!只好改为《年轻的城》。我和权策设计的封面,那时候很喜欢抽象派画家保罗·克利,所以封面做的极其简约,如儿童的稚笔画。

我和永波的诗歌写作,也在这时达到高峰,基本是一个月写一大本,并时常一高一低地出现在陕西各大高校的文学沙龙及朗诵会现场,那时每到一处,我都以演说家的激情滔滔布道,永波则沉默地站一旁,用他的话讲“阴沉的像一把左轮手枪”。

1985年我毕业留校,在学报编辑部工作,我的单身宿舍更是成了星火社诗人的聚会的据点。那时,因为学校经费紧张,《年轻的城》已被迫停办。我和永波就只好或单独或合集复印出了几本诗集:《寂静》、《皇帝》、《影子的慢板》等。1986年7月永波毕业,做为一个软件专业的毕业生,居然被分配到哈尔滨车辆厂的技术科,让我隐隐有些担忧。火车站分别时,我们相互重重叮嘱,一定要相互激励,抱团打拼,在中国当代诗坛杀出一条血路。

后来,我深感自己的诗歌写作出现瓶颈,无法从自我成型的局限中突破超越,于是转而投奔我喜欢的另一领域——电影。而永波则在诗歌的荆棘之途孤军奋战、愈行愈远。1991年香港文光出版社的新世纪诗人丛书出版了他的第一本诗集《红鸟》,有一首怀念父亲的悼亡长诗《给故去的父亲》引起高度关注,它标志着永波的诗歌写作进入一个更高的阶段。果然,进入九十年代,他诗歌的技艺愈发炉火纯青,个人创作达到巅峰,尤其是几十部长诗的出炉,使其昂然步入当代中国最重要的诗人行列。1999年台湾唐山出版社的大陆先锋诗丛出版了他的第二本诗集《两种速度播放的夏天》,主编黄梁对他的评价非常准确:“马永波的诗,清肃、大方。精神主体坚实磁场开阔,富有北方寒地清冽的气息,为汉语诗歌开拓了一个辽阔的无法估量的神秘诗境。”2015年他的第三本诗集,也是他在大陆的第一本诗集《词语中的旅行》出版,我特意在西安——他诗歌写作的故乡主持举办了一场研讨会和两场朗诵会,算是对他多年诗歌创作的一次总结和回顾!

去年,我和永波开始谋划拍摄一部以永波诗歌为主题的诗电影,电影名沿用他诗集的名字《词语中的旅行》。影片将以诗人的诗句贯穿,展示诗人精神世界的进化和成长,通过童年、青春、现实的三重时空,深刻展示社会巨变在诗人命运的中留下的印记,以及诗人对生命存在的沉思与冥想。

我当然知道在如此商业化和娱乐化当代中国,想完成这样一部极端另类的艺术电影何其艰难,但我仍坚信上苍会赐我机会来完成它。

我把这部电影看做是对我们青春誓言和诗歌友情的永恒纪念!

2019年5月5日

Image: In 1986, when Yongbo had just graduated from university, he was by the Songhua River in Harbin, seemingly pondering Confucius’ words: “Time flows away like this, day and night without ceasing.”

love letter to a still blue shirt—for my best friend Yongbo

致一件沉静蓝衫的情书——给我最好的朋友永波

that hasn’t caught the breeze yet, that is not fluttering,

though in the sleeves there is separate movement; sleeves hanging like the

double pendulum of a steady clock.

Long, thin arms will fill them

Stretch them around you and lean on to their elbows,

Extending thin fingers into a pen.

The colour is as unobtrusive as morning mist rising over the back of the city fox,

that must still be there,

first crossing my path at midnight,

as persistent as nature is in cities,

it’s gentle feet on the same pavement.

And somewhere a boy is constructing his future from blue woven thread,

nevertheless; stretching his arms

2nd April 2025

written after Yongbo explained to me the significance of an event which subsequently altered the direction of his early poetry career and his university selection : the distraction of a surprise love letter placed in his desk by an admirer, shortly before college entrance examination , with a persistent high fever, he performed poorly in the exam and failed to get into the Department of Chemistry at Peking University, which he had long been longing for. Since then, the world has lost a useful chemical engineer and gained a poet who believes that “uselessness is the greatest usefulness”(from Zhuangzi). A blue robe is a typical Ancient Chinese reference to a poet.

Response Poetry By Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

Response Poetry Translated by Ma Yongbo 马永波

致一件沉静蓝衫的情书——给我最好的朋友永波

love letter to a still blue shirt—for my best friend Yongbo

它尚未捕捉到微风,也没有飘动,

尽管衣袖中有着各自的动静;

衣袖悬垂,如同静止时钟的双摆。

修长的手臂将会把它们填满,

伸开,环绕你,倚在肘边,

纤细的食指延伸成一支笔。

这颜色如同晨雾般不引人注目,

在城市狐狸的背上缓缓升起,

那只狐狸一定还在那里,

午夜时分第一次与我不期而遇,

如同城市里的自然一样执着,

它轻柔的脚步踏在同一条人行道上。

与此同时,某个地方,一个男孩

正用蓝色织线构筑着未来;

伸展开他的双臂……

2025年4月2日

永波向我解释了一个事件的意义,这个事件后来改变了他早期诗歌生涯的方向和对大学的选择:在高考前不久,一位仰慕者在他的书桌里放了一封意想不到的情书,让他分心,甚至高烧不退,结果高考失利,没能考上他梦寐以求的北大化学系。从此,世界失去了一位有用的化学工程师,却多了一位信奉“无用方为大用”的诗人(出自《庄子》)。蓝衫是中国人对诗人的典型指称。

Image: Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨

1980, family home, Dawley, Telford, in the late seventies—she acted, played guitar and tin whistle, wrote her own songs, sung traditional folk songs at The Meadow Folk Club, Ironbridge, run by her uncle, Gerald Hannon, wrote very little poetry but always wanted to write more. On the school syllabus she loved reading Shakespeare—Hamlet/Lear/Tempest, Keats, Gunn, Hughes, Bertolt Brecht. After school reading – her most inspiring play was ‘Waiting for Godot’ by Beckett, loved Yeats, Stevie Smith, Arnold Wesker, Thomas Hardy, Eliot. Favourite book back then was ‘Brave New World’ by Aldous Huxley. Favourite short story was ‘There will come soft rains’ by Ray Bradbury. Favourite movie ‘Alien’ by Ridley Scott. She fully identifies with the idea of “uselessness is the greatest usefulness”(from Zhuangzi)

Image: Ancient Chinese poet wearing a blue robe.

‘Although Helen Plett’s poem ‘love letter to a blue shirt—for my best friend Yongbo’ is set in a modern cultural context, its language and overall style lean toward classical Chinese aesthetics. To highlight the poet’s weariness of modern civilisation, the most appropriate translation should render his “blue clothes” as “chang”—the lower part of the traditional Chinese “upper garment and lower chang” attire for Ancient Chinese men. While “chang” cannot be translated as “skirt,” it is a basic lower-body garment whose form and function are closest to those of a modern skirt. Moreover, it was often paired with upper garments and trousers to form a complete attire system. Their attire contained distinct skirt-like or robe elements.’ Ma Yongbo 马永波, 9th September 2025

Image: Jiaotong University, Xi’an

All images under individual copyright © to either Ma Yongbo 马永波 or Helen Pletts 海伦·普莱茨